ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine: How Strategic Ambiguity Protects Southeast Asia’s Future

Author’s Note

This essay is a long-form strategic analysis designed for readers interested in serious, critical engagement with Southeast Asia’s evolving geopolitical dynamics.

It is not a summary, a news article, or a conventional opinion piece.

It is a structured exploration of the internal logic, external pressures, and future prospects of ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine — built to provide both depth and critical insight.

Readers are encouraged to approach the text not as a passive reading experience, but as an active strategic inquiry:

Where are the fractures?

What adaptations are possible?

What choices must be made?

In a world overwhelmed by noise and acceleration, clarity requires time.

This essay was written in that spirit.

I. Introduction

In a world marked by increasing geopolitical fragmentation, Southeast Asia stands apart.

While other regions are drawn into binary alignments, ASEAN operates differently: it resists absorption into any single orbit.

At the center of this deliberate balancing act lies ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine — an unwritten method of survival through strategic ambiguity, calibrated consensus, and flexible diplomacy.

ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine is not codified in treaties or publicly proclaimed through doctrine papers.

It is a living strategy, visible only through consistent patterns of action: hedging security ties, diversifying economic partnerships, promoting dialogue platforms, and delaying choices when choices threaten to narrow the region’s maneuvering space.

Understanding this doctrine requires grasping ASEAN’s fundamental view of power.

Unlike Western traditions that equate strength with assertion, Southeast Asian strategic culture often equates survival with the management of ambiguity.

Silence, delay, and consensus are not signs of indecision; they are shields against premature entrapment and strategic inflexibility.

The origins of ASEAN’s strategic behavior are deeply rooted.

Colonial fragmentation, Cold War interventions, proxy conflicts, and external ideological pressures have left lasting scars.

From the fall of Saigon to the Cambodian conflict and the Vietnam-China border war, Southeast Asia experienced firsthand the costs of being drawn too deeply into great power rivalries.

ASEAN was created in 1967 not to consolidate power, but to manage vulnerability.

Its founding principles — non-alignment, non-interference, and consensus — were never idealistic statements.

They were calculated instruments for maximizing autonomy in a region permanently exposed to external pressure.

Today, however, ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine faces a world that is changing in dangerous ways.

The intensifying rivalry between the United States and China no longer operates within the predictable frameworks of the Cold War.

New domains — digital infrastructure, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence — create new arenas where ambiguity is harder to sustain.

Internal divergences among ASEAN members, widening in political systems, economic alignments, and threat perceptions, threaten the coherence necessary for the doctrine to work.

Critics often misread ASEAN’s cautious behavior as irrelevance or failure.

This analysis is shallow.

The absence of loud action does not indicate absence of strategy.

This essay examines ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine as a sophisticated survival mechanism — one rooted in memory, maneuver, and adaptive flexibility.

It will explore its historical foundations, operational mechanisms, emerging stress points, and the urgent need for evolution if ASEAN is to remain a relevant actor in a fractured and accelerating world order.

II. Foundations of ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine

The survival instincts embedded in ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine are inseparable from the region’s historical experience with external domination and internal fragmentation.

In contrast to regions forged through ethnic unity, cultural homogeneity, or centralized authority, Southeast Asia’s modern states emerged from a history of overlapping civilizations, colonial interventions, and Cold War battlegrounds.

Rather than uniting under a single hegemon, Southeast Asia developed a survival strategy based on managing diversity under pressure.

The Cold War period (1950s–1970s) was the crucible that shaped ASEAN’s foundational DNA.

During this time, Southeast Asia was not simply a theater of ideological rivalry — it was an active battlefield.

The Vietnam War, the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation (Konfrontasi), insurgencies in Thailand, communist movements in the Philippines and Burma — each internal conflict risked becoming an entry point for superpower escalation.

ASEAN was founded in 1967 by five countries — Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand — with a specific, pragmatic aim: prevent Southeast Asia from becoming a permanent proxy ground for external actors.

The association’s founding principles were not abstract commitments to peace or unity; they were calculated methods for neutralizing vulnerabilities.

Three operational pillars defined ASEAN’s early structure:

1. Non-Alignment

In a world where great powers demanded allegiance, ASEAN rejected formal security alliances.

Instead, each member retained sovereign control over its external relationships while committing informally to regional stability.

This allowed ASEAN states to secure economic or military assistance from external powers without binding the entire bloc to a single external actor’s strategic agenda.

Non-alignment was not idealism; it was strategic insurance against strategic capture.

2. Non-Interference

Given the internal fragility of member states — ranging from insurgencies to unstable post-colonial governments — ASEAN recognized that sovereignty had to be absolute to prevent internal conflicts from spilling over.

Non-interference ensured that ideological, ethnic, or political differences did not become justifications for external interventions, whether by neighbors or by superpowers.

It also preserved ASEAN’s collective flexibility: no member could be forced to take sides in another’s internal crises.

3. Consensus-Based Decision Making

Consensus was a direct defense against great power manipulation.

By requiring unanimity for major actions, ASEAN prevented external actors from exploiting internal divisions to legitimize their ambitions.

It slowed decision-making, but it also ensured that no single member could use ASEAN to pull the entire bloc into an external rivalry.

Consensus was the diplomatic firewall that preserved ASEAN’s autonomy.

Strategic Culture, Not Bureaucratic Accident

These three pillars reflect a strategic culture that prioritizes survival over clarity, flexibility over confrontation, and space over speed.

In Southeast Asia, the lesson of history was clear: strength lies not in loud declarations or binding treaties, but in the ability to navigate external turbulence without losing internal coherence.

ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine evolved directly from these principles.

It was not born of passivity, nor of cultural fatalism.

It was an active, calculated adaptation to a world where small and middle powers survive not by dominance, but by managing contradictions.

Even as the Cold War ended and globalization accelerated, ASEAN did not abandon these instincts.

The post-Cold War expansion — from five members to ten — reinforced the logic that ambiguity, dialogue, and consensus-building were better suited for Southeast Asia’s fragmented realities than any rigid security architecture.

ASEAN’s foundations must be understood not as signs of weakness, but as strategic choices made in a dangerous, contested environment — choices that, for decades, preserved Southeast Asia’s relative autonomy while other regions fractured.

But survival strategies, like the environments they respond to, cannot remain static.

The next sections will examine how ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine is being tested by a new, more complex world order — and why its foundational strengths are now becoming sites of potential vulnerability.

III. Strategic Hedging in Action

While ASEAN’s foundational principles explain the philosophy behind its survival, ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine is most clearly visible through its tactical execution — particularly in the realm of strategic hedging.

In the face of escalating U.S.-China rivalry, ASEAN states do not align firmly with either side.

Instead, they adopt sophisticated balancing strategies that preserve maneuvering space, diversify dependencies, and delay commitments that could constrain future options.

This tactical flexibility operates across two main dimensions: security and economics.

Security Hedging

In the security domain, ASEAN states walk a tightrope.

They engage in defense cooperation with external powers — including the United States, Japan, India, Australia, and increasingly Europe — while simultaneously participating in multilateral platforms that include China.

- Singapore hosts U.S. naval and air assets under the 1990 Memorandum of Understanding but resists any move toward formal alliance structures like NATO.

Its strategic logic is clear: deepen operational security capabilities with external partners without ceding strategic autonomy. - Vietnam has elevated its defense relationships with the United States to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership — the highest diplomatic tier — yet continues to manage its relationship with China through high-level Party channels and cautious, often symbolic, military engagements.

- Indonesia, the region’s largest country, invests in maritime defense modernization with Japanese, South Korean, and American support but actively resists framing these moves as anti-China initiatives, maintaining its identity as a non-aligned regional leader.

ASEAN itself promotes multilateral security dialogues such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the East Asia Summit (EAS).

These platforms force rival powers into structured dialogue, creating diplomatic friction that slows escalation and buys ASEAN members precious strategic time.

Security hedging reflects a brutal calculation: no ASEAN member believes it can single-handedly resist Chinese coercion or fully rely on American guarantees.

Thus, strategic ambiguity becomes the only viable method to maximize optionality.

Economic Hedging

The economic dimension of ASEAN’s hedging is equally sophisticated — and perhaps even more vital.

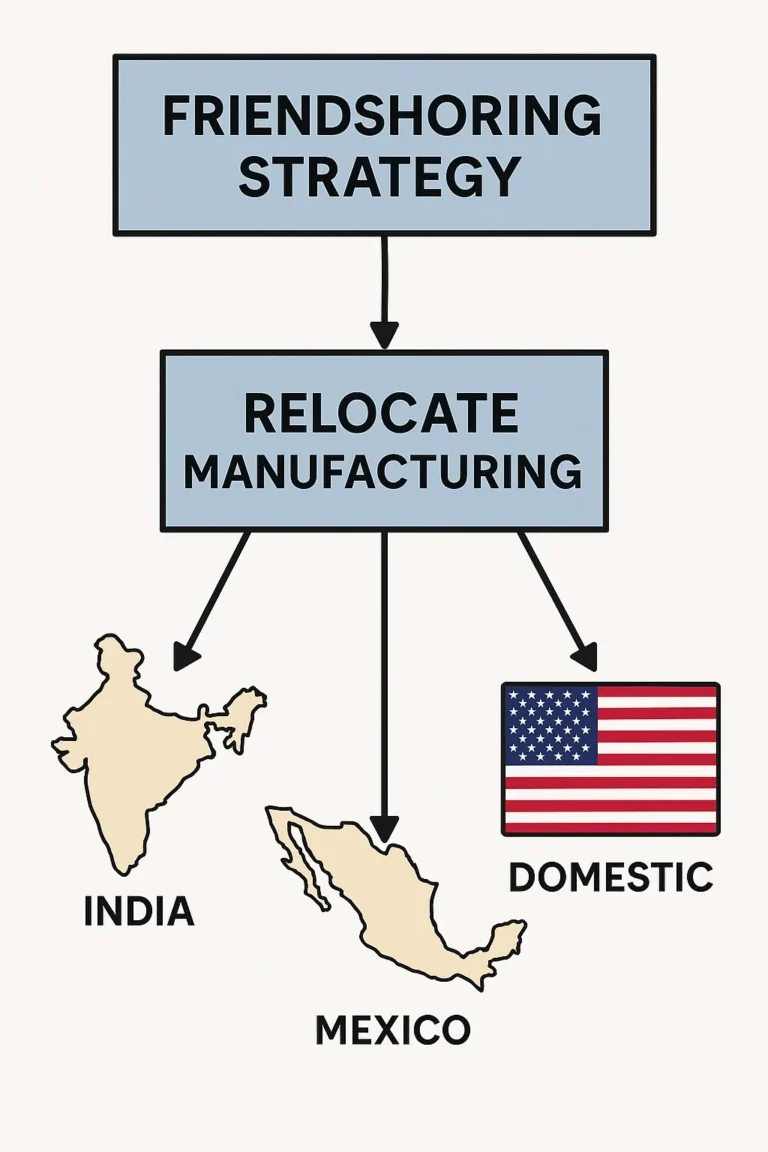

- ASEAN is deeply integrated into China-centric supply chains through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) — the world’s largest free trade agreement, including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and ASEAN.

- Simultaneously, key ASEAN economies like Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore are active members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which notably excludes China but links them with advanced economies like Japan, Canada, Australia, and Chile.

- ASEAN also pursues bilateral trade agreements with the EU, the UK, and India, actively hedging against overreliance on any single market.

This dual-track strategy minimizes economic coercion risks.

It also turns ASEAN into an indispensable node in multiple overlapping economic architectures, enhancing its bargaining power without direct confrontation.

In a practical sense, economic hedging means ASEAN states can shift supply chains, diversify markets, and recalibrate trade strategies if geopolitical tensions escalate — preserving maneuver space in the economic domain just as in security affairs.

Strategic Cases: Hedging as Calculated Action

- Vietnam signed the CPTPP while simultaneously pushing to expand trade with China, demonstrating a dual commitment to economic diversification and neighborhood stability.

It has become one of Asia’s most attractive hubs for supply chain shifts, leveraging tensions without openly antagonizing Beijing. - Indonesia’s balancing between Chinese infrastructure investments (via the Belt and Road Initiative) and its own “Global Maritime Fulcrum” doctrine illustrates how states accept Chinese economic influence selectively while retaining broader strategic independence.

- Singapore actively courts both Western and Chinese tech companies, managing to retain critical digital infrastructure independence while positioning itself as a neutral financial and technological hub.

These examples demonstrate that ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine is not passive neutrality.

It is an active, calculated system of managing external dependencies, mitigating strategic risks, and preserving autonomy under increasingly tight global pressure.

Strategic hedging is the daily operational expression of ASEAN’s deeper doctrine: survive by balancing contradictions rather than eliminating them.

IV. The Role of Silence and Consensus

The operational success of ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine depends on two pillars often misunderstood by external observers: strategic silence and enforced consensus.

Far from being signs of passivity or bureaucratic inertia, these mechanisms are deliberate tools designed to preserve space, manage internal diversity, and delay external entrapment.

Understanding these pillars requires situating ASEAN within a broader Southeast Asian strategic culture — one that values flexibility, face-saving diplomacy, and survival through calibrated ambiguity.

Strategic Silence as Active Maneuver

In Western diplomatic logic, silence often implies weakness, irrelevance, or lack of resolve.

In ASEAN’s strategic culture, silence is an active maneuver — a deliberate choice to preserve maneuvering space when clear positioning would invite premature confrontation.

Silence buys time.

It allows ASEAN members to recalibrate, negotiate internally, and respond flexibly to external changes without locking themselves into rigid frameworks.

Examples of strategic silence at work:

- During the height of the South China Sea tensions in the early 2010s, ASEAN refrained from issuing strongly worded bloc-wide condemnations against China, even after clear provocations.

While criticized for “failing” to stand up to Beijing, this silence allowed individual ASEAN states like Vietnam and the Philippines to pursue bilateral and multilateral legal strategies (e.g., the Philippines’ arbitration case at The Hague) without forcing the entire bloc into a collective confrontation it could not sustain. - In the aftermath of the Myanmar coup in 2021, ASEAN’s muted response was not simply indecision.

It was a reflection of the bloc’s internal calculus: acting too aggressively could have forced member states to openly split, fracturing ASEAN’s unity beyond repair.

By maintaining strategic ambiguity, ASEAN preserved minimal channels of engagement even as internal disagreement simmered.

Strategic silence is therefore not the absence of action.

It is action — action designed to create time, space, and survivability in highly volatile situations.

Consensus as a Strategic Defense Mechanism

Consensus is often caricatured as ASEAN’s “handicap” — slowing decision-making, diluting statements, and preventing timely responses.

But seen through the lens of survival, consensus is a strategic firewall against external manipulation and internal fracture.

In a bloc with vast differences — between maritime and mainland states, democratic and authoritarian regimes, China-leaning and U.S.-leaning economies — consensus ensures that no single member can weaponize ASEAN for external purposes.

Operationally, consensus does three critical things:

- Prevents Major Power Capture

No external power can easily exploit internal ASEAN divisions to legitimize its actions.

Even when individual states lean toward external actors, collective ASEAN action remains bottlenecked by consensus. - Preserves Internal Cohesion

By avoiding public splits, consensus prevents internal disputes from escalating into strategic ruptures that would destroy ASEAN’s credibility and bargaining power. - Delays Polarization

In a rapidly polarizing world, consensus allows ASEAN to slow external pressures to choose sides, preserving neutral maneuvering space longer than would otherwise be possible.

The Cultural Foundation: Harmony Over Confrontation

Southeast Asian diplomatic culture deeply values harmony, flexibility, and face-saving over confrontation and binary choices.

This cultural substrate reinforces ASEAN’s preference for consensus and silence.

In regional cultures shaped by centuries of kingdom rivalries, colonial fragmentation, and external manipulation, direct confrontation is often seen as a failure of leadership, not an assertion of strength.

Survival is achieved through negotiation, flexibility, and the preservation of relationships — even in the face of deep disagreement.

ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine operationalizes this cultural logic at the institutional level.

It is a collective recognition that in Southeast Asia’s environment, the cost of fragmentation is far higher than the cost of slow, sometimes frustrating, diplomacy.

The Costs of Silence and Consensus

While strategic, these tools are not without cost.

- Delayed Responses: ASEAN often responds to crises too slowly to shape events.

- Vague Statements: Diluted declarations sometimes fail to deter aggressors or reassure external partners.

- Internal Frustrations: Member states with stronger interests (e.g., Vietnam or the Philippines in the South China Sea) can become frustrated by ASEAN’s inability to act decisively.

But these costs are calculated.

They are accepted because the alternative — fragmentation, external capture, open splits — would be strategically fatal for the bloc’s collective survival.

Silence and consensus are not bureaucratic accidents.

They are ASEAN’s evolved survival mechanisms — flexible shields built for a region where ambiguity, not confrontation, maximizes strategic space.

As the world fractures more sharply, these tools will be tested harder than ever.

But abandoning them would not make ASEAN stronger; it would remove the very architecture that has allowed it to endure.

V. Stress Tests: Fractures Under Pressure

For decades, ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine has shielded the region from the worst effects of great power competition.

But survival strategies that work under one set of conditions can become liabilities under another.

Today, ASEAN faces structural stress tests that reveal not temporary flaws, but deep contradictions that cannot be ignored.

The fractures are not accidents.

They are the inevitable consequences of a doctrine that depends on internal cohesion and external balance — both of which are now eroding.

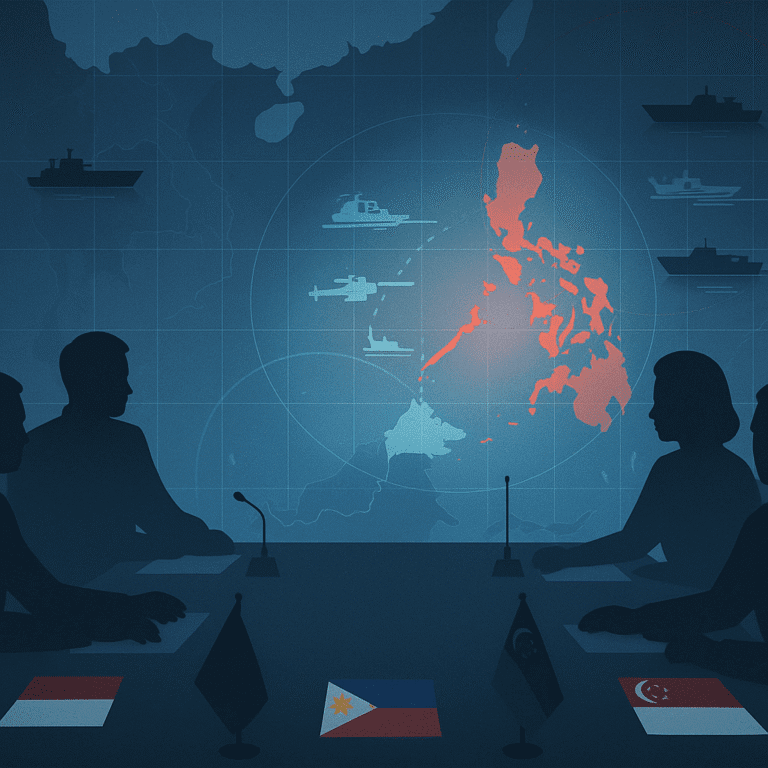

1. South China Sea Disputes: Consensus Weaponized

The South China Sea disputes are the clearest example of ASEAN’s internal contradictions under pressure.

For frontline states like Vietnam and the Philippines, China’s militarization of disputed reefs is an existential security threat.

For mainland Southeast Asian countries like Cambodia and Laos, heavily dependent on Chinese economic and political support, these disputes are remote concerns better left unprovoked.

China has exploited this divergence masterfully.

By cultivating deep bilateral ties with mainland ASEAN states — through infrastructure investments, concessional loans, and elite co-optation — Beijing ensures that any attempt by ASEAN to issue strong collective statements is vetoed from within.

The 2012 ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Phnom Penh — the first in ASEAN’s history to fail to produce a joint communiqué — was a visible crack.

Cambodia, then chairing ASEAN, reportedly blocked any language critical of China, exposing the vulnerability of the consensus model when internal interests diverge sharply.

Strategic Insight:

ASEAN’s consensus model, while effective under balanced pressures, becomes a weapon for external actors when internal cohesion breaks.

If ASEAN continues to demand unanimity on existential security issues, its strategic voice will remain paralyzed exactly when it is most needed.

Solution Angle:

Issue-specific “coalitions of the willing” within ASEAN — allowing flexible diplomatic action without demanding total consensus.

2. Myanmar Crisis: Norms Versus Stability

The 2021 military coup in Myanmar posed a different kind of fracture — a moral and normative crisis.

ASEAN’s response, centered on the Five-Point Consensus, quickly collapsed as Myanmar’s junta disregarded commitments and regional leaders grew divided on how to respond.

The principle of non-interference clashed directly with ASEAN’s need to preserve basic political legitimacy and regional stability.

ASEAN’s muted engagement — barring junta representatives from some meetings but refusing full suspension — angered both domestic publics across Southeast Asia and external partners like the EU and U.S.

ASEAN’s image as a credible diplomatic actor suffered visible damage.

Strategic Insight:

Non-interference was a survival tool when internal political systems were unstable and external threats dominated.

But when a member state’s collapse threatens ASEAN’s legitimacy and regional order, rigid non-interference weakens, not strengthens, the bloc’s survival capacity.

Solution Angle:

Introduce differentiated response mechanisms: maintaining non-interference for routine issues, but allowing collective action thresholds when a member’s actions endanger regional credibility.

3. The Rise of Minilateralism: ASEAN’s Marginalization Risk

The growing prominence of minilateral arrangements — AUKUS, the Quad, Japan-Philippines-U.S. security pacts — reveals another structural stress point.

Faced with urgent security risks, ASEAN states are increasingly bypassing ASEAN frameworks to secure their own strategic interests individually.

The Philippines’ expanded defense arrangements with the United States, Vietnam’s outreach to Japan and India, Indonesia’s closer military dialogues with Australia — all reflect growing doubts about ASEAN’s capacity to protect member interests collectively.

This bypass phenomenon is not hostile to ASEAN — but it is a sign that the bloc is increasingly seen as irrelevant to high-stakes security decisions.

Strategic Insight:

ASEAN’s insistence on full consensus and neutrality is no longer enough to satisfy member states’ rising individual security needs.

If members find credible security guarantees elsewhere, ASEAN risks becoming a symbolic, rather than strategic, actor.

Solution Angle:

Develop layered security cooperation models within ASEAN — allowing voluntary strategic alignments while preserving the broader framework.

The Unavoidable Reality: Fragmentation or Evolution

Across these stress points, a deeper truth emerges:

ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine depends on conditions — internal cohesion and external balance — that are no longer guaranteed.

Without adaptation, the fractures will widen:

- Maritime states versus mainland states.

- Democratic pressure versus authoritarian entrenchment.

- China-leaning economies versus U.S.-leaning strategic interests.

Fragmentation will not come through formal dissolution.

It will come through strategic irrelevance — a gradual bypassing of ASEAN by the real mechanisms of regional security, trade, and digital governance.

The survival of ASEAN’s model depends on one hard choice:

Adapt the doctrine to new realities, or watch it erode silently into obsolescence.

VI. ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine in the Future World Order

The future of ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine will not be determined by ASEAN alone.

It will be shaped by structural shifts in global power, regional dynamics, and internal adaptation — or lack thereof.

Today, as the global order fractures along technological, security, and economic fault lines, ASEAN faces a hard strategic reality:

Ambiguity buys time, but it no longer guarantees survival.

Multipolarity: Opportunity and Risk

The emergence of a multipolar world — with China, the United States, India, Japan, and Europe all vying for influence — superficially favors ASEAN’s hedging strategy.

Multiple external players mean more options, more leverage, and more ability to delay exclusive alignment.

ASEAN thrives when it can maneuver among competing external interests without becoming captive to any single one.

However, multipolarity also carries sharper risks:

- Great powers are increasingly intolerant of ambiguity.

The U.S. demands “clear choices” on Indo-Pacific partnerships.

China punishes hedging behavior through economic coercion. - The competition is no longer confined to military alliances; it now spans technology standards, digital infrastructure, energy transitions, and green supply chains.

In a fragmented world order, the ability to hedge depends not just on diplomatic agility, but on economic, technological, and governance capabilities that ASEAN is unevenly developing.

Strategic Insight:

- Multipolarity offers ASEAN space — but only if ASEAN members can move beyond tactical hedging toward proactive balancing strategies, investing in resilience rather than merely delaying decisions.

Internal Divergence: The Growing Fault Line

Internally, ASEAN’s cohesion is under increasing pressure.

- Economic divergence: Vietnam’s and Singapore’s rapid integration with Western-led trade networks contrasts with Cambodia’s and Laos’ increasing dependence on China.

- Security divergence: Maritime states like the Philippines and Vietnam face existential threats in the South China Sea; mainland states prioritize economic connectivity over maritime security.

- Governance divergence: Political shifts — from democratic pressures in Malaysia to authoritarian consolidation in Cambodia — strain ASEAN’s ability to maintain coherent diplomatic messaging.

These divergences are not tactical disagreements; they reflect deep structural differences in strategic priorities.

Strategic Insight:

- ASEAN’s survival will require institutionalizing flexible geometry — allowing sub-group cooperation (for example, among maritime democracies) without breaking the broader ASEAN framework.

Technological Sovereignty: ASEAN’s Next Battleground

The future competition will not be fought only with ships, soldiers, or economic sanctions — but with control over digital infrastructure, cloud sovereignty, artificial intelligence standards, and critical data flows.

ASEAN’s technological fragmentation is dangerous:

- Some members lean heavily toward Chinese technology ecosystems (e.g., Huawei, ZTE).

- Others — notably Singapore and Vietnam — are pivoting toward U.S.-aligned cybersecurity frameworks and data governance norms.

Without collective standards, ASEAN risks becoming a checkerboard of external digital dependencies — compromising its autonomy.

Strategic Insight:

- ASEAN must treat technological sovereignty as a core survival issue — on par with trade and security.

- Developing ASEAN-wide standards for 5G, AI ethics, cybersecurity resilience, and data governance is no longer optional — it is existential.

Scenario Mapping: 2030 and Beyond

Based on these dynamics, ASEAN faces three plausible futures:

| Scenario | Description |

| Resilient Autonomy | ASEAN upgrades its mechanisms: flexible integration, crisis response, technological sovereignty frameworks. It remains a relevant balancing actor in a fractured Indo-Pacific. |

| Silent Fragmentation | ASEAN formally survives, but functional cooperation erodes. Real strategic decisions shift to minilateral alliances and external pacts, bypassing ASEAN frameworks. |

| Strategic Capture | External powers deepen client relationships with individual ASEAN states, fragmenting the bloc’s autonomy. ASEAN becomes increasingly irrelevant to regional strategic calculations. |

What ASEAN Must Do

To avoid erosion, ASEAN must:

- Institutionalize flexible coalitions: Issue-specific cooperation clusters within the ASEAN framework.

- Upgrade crisis response capabilities: Create thresholds for rapid collective action when regional stability is threatened.

- Assert technological sovereignty: Build collective capacity for digital infrastructure, cybersecurity, and AI governance.

- Invest in strategic foresight: Anticipate next-generation fault lines (e.g., quantum tech, climate security) before external actors impose frameworks.

ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine still offers the region a survival blueprint — but only if it is transformed from a passive shield into an active instrument of strategic construction.

Flexibility must be sharpened by resilience.

Ambiguity must be upgraded into controlled, deliberate maneuvering.

Otherwise, ASEAN risks becoming a relic of an older, slower world — outpaced by the fractured realities of the new one.

VII. Conclusion: Survival Through Strategic Ambiguity

For more than five decades, ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine has shielded Southeast Asia from the destabilizing gravitational forces of great power competition.

Through strategic ambiguity, consensus-based diplomacy, and flexible engagement, ASEAN has preserved a rare zone of relative autonomy in an increasingly contested world.

But survival strategies, no matter how carefully crafted, are not timeless.

Today’s geopolitical environment is fundamentally different from the Cold War and post-Cold War periods that shaped ASEAN’s behavior.

The rise of assertive multipolarity, the weaponization of technological dependencies, and the growing divergence among ASEAN’s own members expose the limits of a doctrine built for a slower, more compartmentalized world.

Critics who dismiss ASEAN’s ambiguity as weakness misunderstand the sophistication behind its restraint.

Flexibility under pressure, silence amid provocation, and consensus amid diversity are hard-won skills — the result of historical experience, not indecision.

Yet the deeper truth is that strategic ambiguity alone is no longer enough.

Flexibility without structural adaptation becomes fragility.

Silence without recalibration becomes irrelevance.

Consensus without differentiated mechanisms becomes paralysis.

If ASEAN wishes to remain a meaningful actor in shaping Southeast Asia’s future — rather than being shaped by external forces — it must evolve its Quiet Doctrine into an active doctrine of strategic construction.

This evolution demands:

- Flexible integration models that allow sub-coalitions to act without fracturing the bloc.

- Crisis response frameworks that move beyond unanimity in existential emergencies.

- Technological sovereignty initiatives that protect digital autonomy from becoming the next arena of strategic capture.

- Strategic foresight institutions that anticipate, rather than react to, fractures in global order.

The choice facing ASEAN is stark:

Adapt now — deliberately, structurally, and strategically — or fade quietly into the background noise of minilateral coalitions, bypassed frameworks, and external dependency.

In a fractured 21st-century world, survival will not belong to the loudest actors.

It will belong to those who master the art of maneuver within ambiguity — who can wield flexibility not as a defense of the status quo, but as a weapon for shaping the future.

ASEAN’s greatest asset — its Quiet Doctrine — remains a potent tool.

But only if its silence becomes deliberate signal, its flexibility becomes structured resilience, and its consensus becomes the foundation for active, not reactive, regional agency.

The next decade will determine whether ASEAN remains a strategic player — or becomes a symbolic memory.

Stay Ahead. Think Deeper. Move Smarter.

If this analysis helped sharpen your understanding of Southeast Asia’s future, imagine what the next layer could offer.

Subscribe to VietFuturus to access strategic essays, early intelligence dispatches, and deeper insights into the fractures and futures shaping the region.

2 Comments