Digital Sovereignty in Southeast Asia: Between Opportunity and Occupation

Digital Sovereignty in Southeast Asia – key reseảch topic of our Strategic Ambiguity Division

Executive Takeaways

- Digital sovereignty is no longer abstract — it is the new frontline of strategic autonomy in Southeast Asia. Infrastructure, platforms, and protocols now determine who governs and who complies.

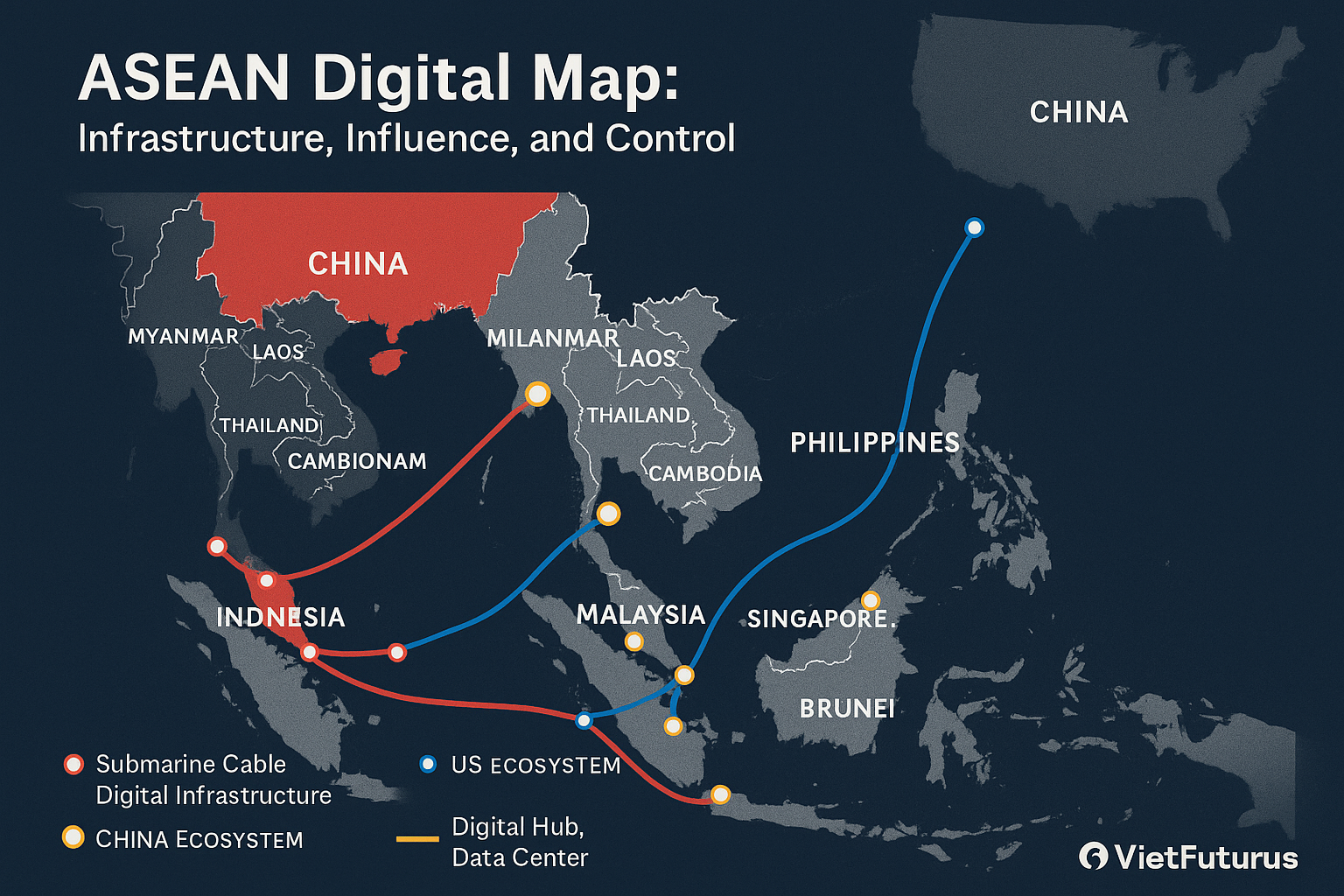

- China’s Digital Silk Road has quietly entrenched itself across Southeast Asia by offering full-stack systems — from cables to cloud — with strategic lock-in, especially in weaker ASEAN states.

- The U.S. and allies offer open alternatives, but their frameworks often come with strategic expectations and vendor lock-in of their own. Neither ecosystem offers true independence.

- ASEAN is digitally fragmented, lacking shared standards, defensive frameworks, or institutional capacity. This fragmentation makes regional security impossible and sovereignty hollow.

- Vietnam, Singapore, and Indonesia offer three emerging models of response — secure-first, governance-centered, and scale-driven. Together, they could anchor a new digital backbone for the region.

- Risks are immediate and structural: kill switch diplomacy, surveillance by proxy, platform dependency, and irreversible vendor entrenchment. Occupation is no longer military — it is infrastructural.

- Three paths lie ahead: (1) status quo decay via fragmented dependency, (2) minilateral tech coalitions for pragmatic resilience, or (3) a Digital Non-Alignment Doctrine that rebuilds ASEAN sovereignty from the ground up.

- This is the last strategic window for Southeast Asia to define its digital future. Delay will convert sovereign states into client systems — governed not by policy, but by code they didn’t write.

I. Introduction: Why Digital Sovereignty Now?

In Southeast Asia, a new struggle is unfolding — not in war rooms, not across disputed waters, but deep inside cloud servers, undersea cables, and digital regulatory frameworks. It is a struggle over digital sovereignty, and it may prove to be the defining security challenge for the region in the 21st century.

Until recently, digital development was framed primarily as a growth opportunity. Governments prioritized connectivity, innovation, and foreign investment in telecommunications and digital platforms. Infrastructure was technical, not strategic. But that era is over.

Today, every aspect of digital infrastructure — from 5G hardware and cloud data centers to AI frameworks and submarine cables — has become a site of geopolitical tension. Technology is no longer neutral. The architecture of information flow is now inseparable from the architecture of power. And in Southeast Asia, that architecture is being built from the outside in.

At the center of this shift is the rising contest between China and the United States — and their competing digital ecosystems. China’s Digital Silk Road strategy has embedded its infrastructure, platforms, and standards into the fabric of multiple ASEAN economies. From smart cities in Cambodia to backbone networks in Laos and Myanmar, Chinese technology has become the invisible scaffolding of digital life in some member states.

The United States, along with allies such as Japan, Australia, and the EU, has begun to respond. Through initiatives like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and efforts to promote “trusted connectivity,” the West is attempting to offer Southeast Asian nations a non-Chinese alternative. But these initiatives often come with strategic expectations of alignment and increased scrutiny.

Caught between these forces, ASEAN finds itself exposed. Despite decades of hedging and diplomatic flexibility, the region’s digital dependencies are growing faster than its digital capacities. Most ASEAN states lack comprehensive strategies for cloud sovereignty, critical infrastructure resilience, or data governance alignment. The bloc itself has no unified framework for digital security, infrastructure standards, or AI regulation.

This fragmentation is more than a governance issue. It is a sovereignty risk. In a region where conventional military threats remain low-probability but high-consequence, the most likely form of external control will not come through invasion — it will come through infrastructure.

Digital sovereignty, in this context, is not just about privacy or consumer protection. It is about strategic survival.

- Who builds your networks can access your data.

- Who hosts your cloud can shape your commerce.

- Who writes your code can see your decisions before you make them.

This essay explores the current state of digital sovereignty in Southeast Asia, beginning with China’s strategic entrenchment and the West’s counter-response. It will analyze the fractures within ASEAN, examine three critical case studies (Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia), and outline the core risks associated with digital dependency.

Most importantly, it will argue that ASEAN must move from reactive development to proactive design — or risk trading its geopolitical ambiguity for digital subservience.

II. Anatomy of Digital Sovereignty

In Southeast Asia, digital sovereignty is often treated as a vague aspiration — mentioned in official statements, but rarely defined with operational clarity. That ambiguity is dangerous.

To understand the stakes, policymakers must grasp that digital sovereignty is not a single system or policy. It is a strategic architecture composed of interlocking layers. Each layer — if left externally controlled — becomes a vector for influence, surveillance, or coercion. Together, they determine whether a nation governs its digital future or becomes governed by it.

1. Physical Infrastructure: Who Builds the Backbone?

At the base of digital sovereignty lies physical control over the infrastructure:

- Submarine cables

- Cell towers

- 5G hardware

- Data centers

Ownership and operational access to this infrastructure determine who can intercept, degrade, or cut digital flow in crisis scenarios.

Current challenge: Much of Southeast Asia’s physical infrastructure is financed, built, or maintained by external actors — especially Chinese firms. This creates long-term exposure to backend control mechanisms invisible to the public but accessible to state-aligned corporate entities.

2. Cloud and Data Sovereignty: Where Does Information Live?

The second layer involves the location, governance, and legal jurisdiction of data.

Even if a nation owns the wires, if its cloud platforms are foreign — Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Huawei Cloud — it does not control its data environment.

Why it matters:

- Data stored in foreign-owned clouds is vulnerable to extraterritorial legal requests (e.g., U.S. CLOUD Act, China’s National Intelligence Law).

- Critical government or financial data can be accessed, paused, or manipulated during a geopolitical crisis — without warning.

Some ASEAN states have begun implementing data localization laws, but enforcement remains inconsistent and loopholes abundant.

3. Platform Sovereignty: Who Mediates the Digital Public?

Southeast Asia’s digital economy is dominated by a small set of foreign-owned platforms:

- Social media (Meta, TikTok)

- E-commerce (Shopee, Alibaba, Amazon)

- Fintech (Alipay, Grab, GCash)

Control over these platforms means control over digital discourse, behavioral data, and transaction patterns. The algorithms that curate what people see, buy, and believe are designed in Silicon Valley or Shenzhen — not Jakarta, Hanoi, or Manila.

Strategic risk: If the domestic digital economy is shaped by external platform logic, local policy becomes reactive by default.

4. Technical Standards and Protocols: Who Writes the Rules of Code?

Beneath the infrastructure and platforms lie the technical standards:

- Encryption frameworks

- Internet routing protocols

- AI governance rules

- 5G security baselines

These standards determine how secure, interoperable, and open digital systems are. The battle to define them is now happening at international bodies like the ITU, ISO, and ASEAN’s own ICT committees.

China is aggressively promoting its New IP protocol. The U.S. and allies push for open, interoperable systems. ASEAN lacks a coherent response — and risks adopting by default, not design.

5. Strategic Implication: Sovereignty Is a Stack

Digital sovereignty is not one decision — it is a stack of interrelated dependencies.

- Lose the cables, lose redundancy.

- Lose the cloud, lose control.

- Lose the platform layer, lose public space.

- Lose the standards, and your entire system becomes a derivative of someone else’s vision.

In this landscape, sovereignty is not declared — it is embedded.

Closing Insight for Policymakers:

A state may fly its flag, print its currency, and hold elections — yet be digitally colonized at the backend.

True independence in the 21st century means governing the invisible layers of power.

III. China’s Digital Silk Road: Entrenchment by Design

The previous section outlined how digital sovereignty functions as a layered architecture — and how Southeast Asia’s exposure across those layers increases strategic vulnerability.

The most entrenched actor exploiting these exposures is not theoretical. It is China.

Through the Digital Silk Road (DSR) — the technological arm of the Belt and Road Initiative — China has embedded itself deeply into Southeast Asia’s digital foundations. This strategy is not accidental. It is precise, long-term, and asymmetrically powerful.

1. Infrastructure First: The Foundation of Quiet Control

China’s digital footprint in ASEAN began with the basics: build the infrastructure.

Chinese firms like Huawei, ZTE, China Mobile, and China Telecom have built or financed large portions of the region’s:

- 4G/5G mobile infrastructure

- Fiber optic networks and submarine cables

- National data centers and cloud platforms

- Surveillance-enabled smart cities

These deployments were often faster and cheaper than Western counterparts. For cash-strapped states like Laos or Cambodia, the decision was not ideological — it was financial and immediate.

But the strategic effect is enduring.

Once Chinese infrastructure is in place, reversing it is prohibitively costly — politically, economically, and technologically.

2. Embedded Governance: From Networks to Norms

What makes the Digital Silk Road different from earlier forms of infrastructure aid is its governance layer. China doesn’t just build systems — it embeds its technical standards and operational protocols within them:

- Network management platforms with built-in surveillance capabilities

- Proprietary encryption and routing systems tied to Chinese cloud services

- Maintenance agreements that require ongoing Chinese technical personnel or software dependencies

In effect, the state cedes not just the hardware — but the operational autonomy.

China’s model offers a turnkey state surveillance system — attractive to authoritarian-leaning regimes seeking social control tools. In places like Myanmar (post-coup), this becomes a force multiplier for domestic suppression.

3. Case Studies in Entrenchment

Laos:

China built and now maintains large portions of Laos’ national telecom backbone. Huawei Cloud supports government services, and Chinese fintech apps are widely used. Laos’ digital policy is now functionally aligned with Beijing — without needing formal alignment.

Cambodia:

Smart cities in Phnom Penh are equipped with Huawei surveillance and traffic control infrastructure. The proposed Funan Techo Canal — partially a logistics route — also doubles as a potential dual-use communications corridor.

Myanmar:

After the 2021 coup, the military rapidly expanded Chinese-enabled surveillance and content filtering infrastructure. Huawei and ZTE are known suppliers, enabling regime control over domestic networks and platforms.

4. The Quiet Nature of Occupation

Beijing rarely frames these deployments as strategic assets. The language is developmental: digital inclusion, connectivity, South–South cooperation. But the real effect is what analysts call digital entrenchment — a position from which it is difficult to dislodge external influence without triggering internal disruption.

There is no need for open control.

When a state’s entire backend is built by one actor, coercive leverage becomes ambient.

In a crisis scenario, digital access, network speeds, or cloud services can be subtly degraded — or data flows silently exfiltrated. The target state may not even realize it until the damage is done.

5. The ASEAN Problem: No Counter-Architecture

ASEAN has no unified framework to counter this entrenchment.

Unlike in the security domain, where ASEAN-led platforms attempt to balance great power influence, the digital domain remains bilateral and fragmented. One country’s entrenchment becomes the region’s vulnerability.

The DSR is not just creating dependent clients — it is structurally undermining ASEAN’s collective digital security.

Strategic Insight for Policymakers:

China’s digital entrenchment doesn’t need to dominate headlines — it dominates infrastructure.

By the time a government feels the need to resist, it is often already captured — through routers, not rhetoric.

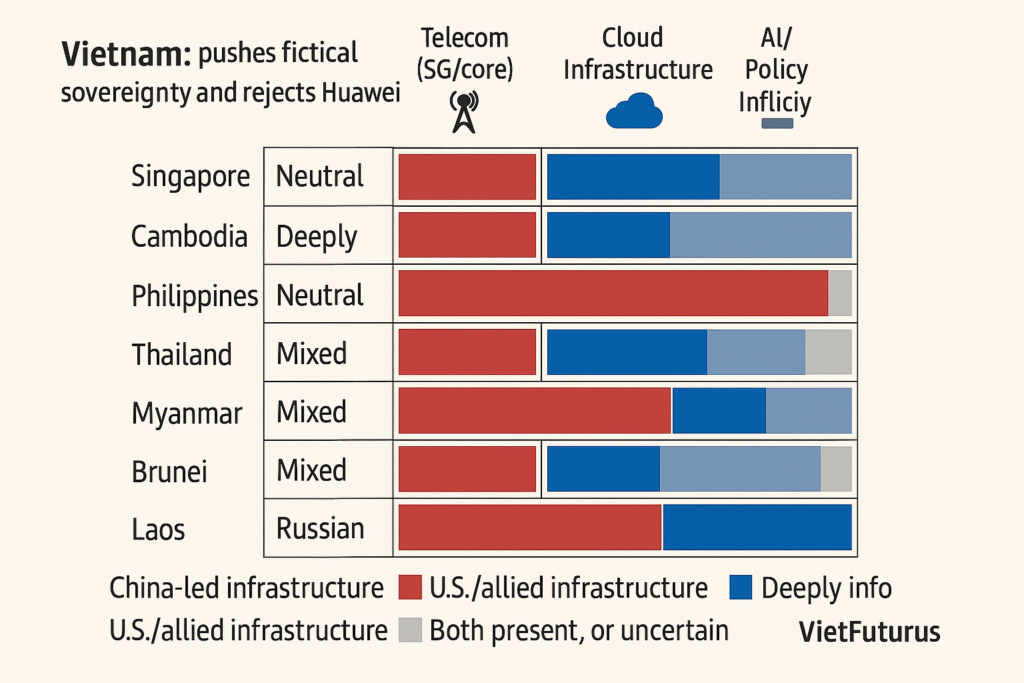

|

Country |

Telecom (5G/Core) |

Cloud Infrastructure |

Data Governance |

Ai/Policy Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Vietnam |

U.S. leaning (No Huawei) |

AWS, Google |

Local control, Western-aligned |

Drafting AI framework |

|

Singapore |

Neutral |

AWS, Azure, Alibaba |

GDPR-compatible |

Leading AI ethics |

|

Indonesia |

Mixed |

AWS, Huawei |

Emerging |

U.S. and China influence |

|

Cambodia |

Chinese |

Huawei Cloud |

Chinese-aligned |

Smart city model (China) |

|

Laos |

Chinese |

Chinese-only |

No regulation |

None |

|

Malaysia |

Mixed |

Google, Azure |

Draft stage |

Passive |

|

Philipines |

U.S. leaning |

Google, Azure |

Pro-West |

Pro-U.S. |

|

Thailand |

Mixed |

Mutiple |

No clear framework |

Low activity |

|

Myanmar |

Chinese |

Chinese |

Military-controlled |

Surveilliance-heavy |

|

Brunei |

Neutral |

Minimal |

Passive |

Minimal |

China vs. U.S. Digital Infrastructure Table

IV. The U.S.–Allied Pushback: Open Tech, Closed Expectations

If China’s Digital Silk Road represents entrenchment through infrastructure, the response from the United States and its allies aims to reassert influence through standards, trust, and conditional access. The contest is no longer just about who builds — it’s about who defines the rules of digital governance.

Following years of reactive posture, the West has begun to align its digital diplomacy around a unified objective: prevent Southeast Asia from becoming structurally dependent on Chinese technology ecosystems.

The result is a surge of counter-initiatives that promote open architecture, secure networks, and transparent governance — but with clear expectations about strategic alignment.

1. The Architecture of Trust: Open, Interoperable — and Geopolitical

At the heart of the Western response is the promotion of a “trusted connectivity” framework.

This includes:

- The Clean Network Initiative (originally U.S.-led): excludes Huawei and other “untrusted vendors” from core digital infrastructure.

- Japan–U.S.–Australia Infrastructure Financing Mechanisms: co-financing subsea cables and telecom networks in the Pacific and parts of ASEAN.

- Digital Partnership Agreements (DPAs): such as those signed with Singapore and, more recently, under negotiation with Vietnam and Indonesia.

These initiatives emphasize openness, interoperability, and digital rights — in contrast to China’s model of tightly integrated, state-aligned control.

But openness has its own boundaries.

Participation in these frameworks often requires adopting Western-aligned data governance norms, surveillance restrictions, and cyber resilience protocols — many of which are implicitly tied to strategic positioning.

2. The Allies’ Advantage: Coordination and Capacity Building

The U.S. doesn’t act alone. Its allies — particularly Japan, Australia, and the European Union — play central roles in Southeast Asia’s digital future:

- Japan leads in digital infrastructure financing and AI ethics standardization, especially in Vietnam and Indonesia.

- Australia offers technical assistance for cybersecurity and network security architecture.

- The EU pushes regulatory convergence via the GDPR model, influencing ASEAN’s fragmented data laws through soft power.

Together, these actors create a parallel digital ecosystem that competes with China not just technologically — but normatively.

3. Risks of Re-Dependency: The Architecture Is Different, But the Leverage Remains

While Western offerings promise transparency and shared standards, they are not devoid of strategic tradeoffs.

- Vendor lock-in still exists: using U.S. cloud services like AWS or Microsoft Azure centralizes control outside the region.

- Geopolitical pressure can surface: the Clean Network, for instance, positioned countries as either “trusted” or not — a binary Southeast Asia historically avoids.

- Surveillance dilemmas persist: although less overt, Western agencies retain significant extraterritorial capabilities (e.g., Five Eyes).

For ASEAN states that prize strategic ambiguity, these frameworks sometimes appear as a different flavor of dependence — one with better branding but similar constraints.

4. Vietnam and Singapore: Strategic Tension Within Alignment

Vietnam has cautiously deepened its engagement with U.S.-aligned frameworks:

- Signed the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with the U.S.

- Cooperating with Japan and Australia on secure telecom infrastructure

- Hosting Google Cloud’s regional operations

Yet Vietnam refuses to fully abandon its non-alignment posture — it does not ban Huawei outright and maintains tech dialogue with China.

Singapore, as always, positions itself as a trusted, neutral hub:

- Engages with AWS, Google, and Microsoft for cloud services

- Leads regional discussions on AI governance

- Yet still cooperates with Huawei on infrastructure where needed

This partial alignment model is what other ASEAN states observe closely — trying to emulate its flexibility without inviting retaliation.

5. The Strategic Message is Subtle, But Clear

The West’s pitch to ASEAN is not “join us or else.” It’s:

“If you want long-term trust, security, and global interoperability — you need to pick our stack.”

But even that soft sell contains hard tradeoffs.

Strategic Insight for Policymakers:

Southeast Asia now faces two ecosystems — neither of which allow complete independence.

While China offers hardware-first entrenchment, the U.S. alliance offers standards-first integration.

In both cases, sovereignty is traded for stability.

The only question is on whose terms.

V. ASEAN’s Fragmented Terrain: No Tech Consensus, No Defense

While China and the United States race to shape Southeast Asia’s digital future, the region’s greatest vulnerability lies within: ASEAN has no unified digital sovereignty strategy.

The bloc that once mastered consensus diplomacy now finds itself digitally incoherent — divided by mismatched laws, competing infrastructures, and incompatible political visions.

In the analog era, this fragmentation was survivable.

In the digital era, it is strategic exposure at scale.

1. The Legal Landscape: Patchwork Governance, No Regional Spine

ASEAN lacks a binding regional digital framework.

Each member state has developed — or failed to develop — its own data protection laws, cybersecurity policies, and digital trade regimes.

- Vietnam has strict data localization rules and tight state oversight.

- Singapore promotes open cross-border data flow under strong compliance safeguards.

- Indonesia passed a personal data protection law in 2022 but enforcement remains weak.

- Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar operate without robust digital rights protections or transparent legal oversight.

The result: Data is governed unevenly. Platforms adapt country by country. Cross-border digital cooperation is legally fragile, and regional resilience is nonexistent.

This lack of legal alignment invites external shaping.

Foreign actors can pick the most favorable regulatory environments for deployment — exploiting regional asymmetry to entrench themselves.

2. Infrastructure Incompatibility: Fragmentation at the Backend

ASEAN states are building networks on different architectures:

- Some countries (e.g., Laos, Cambodia) rely heavily on Chinese vendors.

- Others (Vietnam, Singapore) are actively diversifying or banning certain Chinese hardware.

- 5G rollouts vary wildly: some driven by national champions, others fully outsourced.

This technological heterogeneity prevents regional security synchronization.

One nation’s “safe” vendor may be another’s “threat vector.” There is no region-wide benchmark for digital infrastructure trust.

Strategic consequence: ASEAN cannot meaningfully defend itself as a bloc against supply chain sabotage, state-sponsored cyberattacks, or infrastructure manipulation — because it lacks a shared baseline.

3. Political Asymmetry: Trust Divergence Within the Bloc

Digital strategy is not just technical — it is political.

ASEAN’s member states vary dramatically in how they view:

- Surveillance

- Civil liberties

- State control vs open innovation

- Alignment with external powers

Authoritarian-leaning governments see value in Chinese-style digital control systems.

Democracies — or aspiring democracies — lean toward Western openness, transparency, and citizen rights.

This political divergence makes regional agreement on issues like AI ethics, cyber law enforcement, or digital rights nearly impossible.

Without shared values, there can be no shared digital future.

4. ASEAN’s Existing Mechanisms: Too Weak, Too Slow

ASEAN’s official ICT bodies — such as the ASEAN Digital Ministers’ Meeting (ADGMIN) or the e-ASEAN Framework Agreement — exist, but they are:

- Non-binding

- Diplomatically cautious

- Functionally reactive

They lack the authority, speed, and enforcement capability to drive a unified digital agenda.

While declarations are made, standards are not adopted, platforms are not interoperable, and crises are not coordinated.

5. Strategic Fallout: ASEAN Is a Digital Checkerboard

In practice, Southeast Asia functions as a checkerboard of digital dependencies.

Some countries are plugged into Beijing’s cloud. Others rely on AWS. Some use Huawei routers. Others ban them. Some have cybersecurity laws. Others don’t.

This fragmentation makes collective digital resilience impossible.

A cyberattack on one state cannot be jointly analyzed or responded to.

A regional data breach cannot be collectively addressed.

An AI governance scandal in one jurisdiction creates spillover trust damage across the rest.

Strategic Insight for Policymakers:

The greatest threat to ASEAN’s digital future is not foreign interference.

It is the region’s failure to act as a system.

Without internal alignment, even the best external partnerships will collapse under asymmetry.

Digital sovereignty must be regional — or it will be outsourced.

VI. Strategic Profiles: Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia

ASEAN’s fragmented digital terrain, as outlined in the previous section, leaves the region structurally vulnerable.

But not all member states are passive in this shift. A few are quietly building sovereign digital postures that may offer future models — or cautionary lessons.

Among them, Vietnam, Singapore, and Indonesia stand out. Each represents a different approach to navigating great power pressure, infrastructure dependency, and digital autonomy. Together, they form a potential strategic triangle capable of anchoring ASEAN’s digital future — if they can align.

1. Vietnam: Strategic Balancing in Code

Vietnam has emerged as one of Southeast Asia’s most determined actors in asserting digital sovereignty — not through declarations, but through action.

Key moves:

- Banning Huawei from key telecom infrastructure since 2019.

- Promoting domestic cloud services and tightening data localization rules.

- Passing cybersecurity laws requiring foreign platforms to store data locally and take down “toxic” content.

- Hosting major Western players — Google Cloud, Amazon, Microsoft — while still maintaining open channels with China.

Vietnam views digital autonomy as a national security issue, not just a regulatory concern.

Its strategy mirrors its broader foreign policy: non-alignment with hard edges — balancing global partnerships while protecting critical systems from foreign control.

Strategic tension: Vietnam’s push for local control risks creating regulatory friction with international partners, particularly around content moderation, surveillance, and transparency. But for Hanoi, control is non-negotiable.

Leadership potential: High. Vietnam’s clear red lines and growing digital infrastructure capabilities make it a credible voice for regional digital resilience — if others follow its lead.

2. Singapore: The Digital Diplomat

Singapore plays a different game.

It positions itself not as a digital fortress, but as a trusted intermediary — enabling interoperability, legal clarity, and innovation leadership.

Key moves:

- Hosting data centers for all major global cloud providers.

- Pioneering Digital Economy Agreements (DEAs) with countries like Australia, the UK, and Chile.

- Leading regional efforts on AI governance, cross-border data flow, and digital standards.

- Emphasizing public-private collaboration in cybersecurity and fintech regulation.

Singapore does not block Huawei, nor does it fully embrace any single camp.

Its approach is agnostic but proactive — seeking to shape the rules of engagement rather than choosing sides.

Strategic tension: Singapore’s openness makes it reliant on foreign infrastructure and compliance-heavy partnerships. In crisis scenarios, it may face limited maneuvering space if foreign actors politicize digital access.

Leadership potential: Exceptional — but only as a norm-setter and convener, not a regional defender. Singapore’s influence lies in frameworks, not firewalls.

3. Indonesia: Caught in the Middle

Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy and digital user base, has both the potential and the responsibility to lead — but remains strategically indecisive.

Key moves:

- Introducing a Personal Data Protection Law (PDP) in 2022.

- Collaborating with both Chinese and Western firms across cloud, telecom, and fintech sectors.

- Hosting major AI and e-commerce innovation hubs — while lagging in enforcement.

Indonesia’s digital terrain is expansive but uneven.

Its regulatory institutions are still consolidating power. Infrastructure is a patchwork of foreign deployments. Cyber capacity is underdeveloped. Political will is often reactive, not anticipatory.

Strategic tension: Indonesia wants to be a digital power, but lacks institutional alignment and urgency. Without reform, it risks becoming a high-value target without a shield.

Leadership potential: Significant — but conditional on internal coherence. If Jakarta harmonizes regulation, enforces data laws, and invests in cyber defense, it could anchor ASEAN’s digital commons.

4. Strategic Triangulation: Can These Three Lead Together?

Vietnam, Singapore, and Indonesia represent three distinct but complementary models:

| State | Model | Strength | Vulnerability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnam | Secure-first | Infrastructure control | Regulatory friction |

| Singapore | Open-leadership | Standards, governance | External dependencies |

| Indonesia | Scale-driven | Market + innovation | Institutional weakness |

Together, they could:

- Create regional digital baselines (e.g., shared cloud standards)

- Push ASEAN to define collective security thresholds

- Lead interoperable data flow frameworks with trust audits

But only if they coordinate — not compete.

Strategic Insight for Policymakers:

The future of ASEAN’s digital sovereignty will not be decided in Bangkok or Manila.

It will be decided by how — or whether — Vietnam, Singapore, and Indonesia choose to lead together.

Their actions will either create a shared foundation — or leave the region permanently divided by foreign systems.

VII. Risks of Digital Occupation: Control Without Invasion

In Southeast Asia’s digital transformation, the most severe risks are not visible — they’re embedded.

The region’s growing dependence on foreign digital infrastructure, platforms, and technical expertise has created a new form of vulnerability: digital occupation. It’s not an event. It’s a condition — and it’s already here in several states.

Unlike conventional occupation, it leaves no trace of boots or border violations. It manifests as coercive leverage built into code, contracts, and cloud infrastructure. Control is exercised silently — until it matters most.

1. Kill Switch Diplomacy: The Threat of Sudden Disconnection

When a country’s data centers, 5G core, and public cloud services are operated by foreign vendors, the threat is not merely espionage — it is interruption.

Strategic scenarios include:

- A territorial dispute triggers “unexpected” degradation of cloud performance.

- Critical e-government portals become unreachable during protests or elections.

- Digital payment systems slow down amid strategic realignment talks with new allies.

No declaration is made. No actor claims responsibility. But the message is received: “You are not in control.”

This kind of latent leverage turns infrastructure into influence — and turns governments into digital hostages during crisis.

2. Surveillance by Proxy: Quiet Access, Lasting Exposure

Across ASEAN, foreign-built surveillance systems — smart city platforms, telecom backbones, national databases — offer external actors persistent visibility into the region’s internal dynamics.

This includes:

- Public sentiment analysis in real time

- Tracking of political figures and activists

- Financial transaction mapping of elites

- Behavioral modeling for influence campaigns

In authoritarian settings, these tools are embraced for domestic control.

In democratic systems, they remain vulnerabilities waiting to be activated — particularly during elections or leadership transitions.

3. Infrastructure Lock-In: Irreversible Entanglement

Digital infrastructure is not modular. It is stacked, specialized, and integrated.

Once a country’s systems — from national ID databases to government cloud to telecom switching — are built on one ecosystem, switching becomes prohibitively expensive:

- Local teams are trained in specific vendor environments.

- Middleware is proprietary.

- Service uptime depends on external technical support.

This is not commercial stickiness — it is strategic capture. Laos, Cambodia, and increasingly Myanmar are textbook cases: their entire digital backbone is dependent on Chinese architecture.

4. Economic Dependency via Platform Dominance

Digital occupation extends beyond infrastructure to platform ecosystems.

Southeast Asia’s daily digital life — buying, paying, communicating — is mediated by:

- U.S. platforms (Meta, Google, Amazon)

- Chinese platforms (TikTok, WeChat, Alipay)

- Regional unicorns with global investors (Grab, Shopee)

This gives foreign actors:

- Control over digital revenue streams

- Leverage through deplatforming or algorithmic suppression

- Strategic influence over what narratives rise — and which are buried

A government challenging platform policies may suddenly see its digital economy stall — not through legislation, but through API throttling, compliance warnings, or content invisibility.

5. Strategic Delay: Sabotage Through Soft Engagement

Not all forms of occupation are coercive. Some are disguised as cooperation.

- Donor-funded “pilot projects” introduce dependency-ridden platforms into public systems.

- Technical assistance embeds external consultants in regulatory bodies.

- Foreign legal templates become the basis for national digital law — with hidden vulnerabilities.

Over time, these engagements hollow out domestic policy space. By the time national leaders seek to assert sovereignty, the cost of change is political, financial, and bureaucratically prohibitive.

Strategic Insight for Policymakers:

Digital occupation does not wear a uniform.

It arrives via fiber-optic cables, smartphone apps, encrypted data centers, and memoranda of understanding.

Its signs are subtle:

- A government afraid to regulate a foreign platform.

- A smart city that can’t explain how its data is routed.

- A national cloud policy drafted by foreign legal teams.

The outcome is severe: a sovereign state with diminished agency, unable to make independent decisions in its own digital space.

Final Warning:

If Southeast Asia fails to act collectively, the region risks becoming a digital proxy zone — where sovereignty is a flag, but not a function.

Occupation today is not imposed.

It is adopted.

VIII. Strategic Futures: Owning or Losing the Digital Future

As the digital battleground intensifies, Southeast Asia must confront a harsh truth:

the region’s geopolitical ambiguity will not translate into digital sovereignty.

The analog tools that once enabled ASEAN’s survival — calibrated silence, non-interference, and consensus diplomacy — are poorly suited for a domain shaped by code, speed, and infrastructure entrenchment. In the digital age, power does not wait for consensus, and sovereignty is not declared — it is built.

The current trajectory will not self-correct. Without urgent recalibration, the region faces a future of irreversible dependency, fragmentary security, and strategic marginalization.

To avoid that, Southeast Asia has three future paths. Each carries its own costs and consequences — but only one allows the region to retain control over its digital future.

1. Fragmented Dependency: The Silent Collapse of Sovereignty

This is the default future — where the region continues as it has for the past decade:

- Bilateral deals with competing powers

- Vendor-driven rollouts without regional coordination

- Incoherent cybersecurity and data governance frameworks

In this model, each state negotiates separately, adopting a patchwork of Chinese infrastructure, U.S. platforms, and foreign regulatory templates. ASEAN digital bodies remain politically polite but functionally toothless.

Consequences include:

- ASEAN becomes a checkerboard of incompatible standards and externally controlled systems

- The digital commons — cloud, AI, payments — is mediated entirely by non-ASEAN actors

- Regional cyber defense becomes impossible due to architecture misalignment

- Platform providers gain the ability to silently enforce policy boundaries

This is not digital transformation. It is digital submission by attrition.

Southeast Asia survives as a market — but not as a sovereign actor.

2. Minilateral Tech Coalitions: Pragmatic Alignment Below the ASEAN Level

Recognizing that ASEAN’s full alignment is politically unfeasible, core actors — Vietnam, Singapore, and Indonesia — can initiate minilateral coalitions: flexible, sovereign-centered cooperation that bypasses regional gridlock.

These coalitions are issue-specific but strategic in impact.

They allow forward-leaning states to build shared:

- Data security protocols

- Secure digital infrastructure standards

- Cyber incident response frameworks

- AI safety and ethics oversight boards

- Joint investments in cloud infrastructure or digital ID platforms

Minilaterals allow speed, specificity, and depth — something ASEAN’s consensus model cannot deliver.

Strategic benefits:

- Gradual emergence of interoperable digital architecture

- Collective bargaining power with U.S. and China

- Shared threat intelligence and cyber-resilience operations

- A middle path between alignment and submission

Caution: These coalitions must remain open and scalable — not club-like. The goal is not to fragment ASEAN further, but to build a digital spine others can connect to.

3. Digital Non-Alignment Doctrine: A Regional Architecture of Sovereignty

This is the high-risk, high-reward strategy — and the only one that redefines power instead of merely managing it.

A Digital Non-Alignment Doctrine calls for a coordinated, regionally-owned infrastructure layer — one that replaces foreign lock-in with architectural independence.

This model requires:

- Building regional cloud services under ASEAN or hybrid public–private control

- Mandating data localization with cross-border protocols owned by ASEAN states

- Developing sovereign operating systems and payment platforms for government services

- Creating an ASEAN Digital Standards Authority to certify trust, resilience, and interoperability

- Funding indigenous AI research with strict security, privacy, and cultural context boundaries

- Creating hard thresholds for foreign control over critical infrastructure (5G, chips, cloud, payment rails)

This doctrine does not mean digital isolation.

It means networked sovereignty: interoperable with the world, but rooted in local control.

Implementation Requirements: What It Takes to Succeed

Political leadership.

No digital future can be built without executive-level clarity. Heads of state must treat digital sovereignty as national security — not tech sector reform.

Technical capability.

Policy is meaningless without infrastructure. This means investing in training, funding open-source ecosystems, and establishing digital infrastructure authorities across ministries.

Public–private alignment.

Governments must partner with trusted local firms, academia, and ethical foreign collaborators — with clear boundaries on national core functions.

Narrative shift.

Digital independence must become a story of pride, agency, and long-term peace — not nationalism or anti-globalism.

Southeast Asia must show that it can be digitally integrated without being digitally owned.

Strategic Failure Points to Avoid

- Overreliance on foreign “development” assistance masked as neutral capacity building

- Short-term wins (faster rollout, cheaper costs) at the expense of long-term autonomy

- Adoption of foreign regulatory templates without institutional maturity to adapt or enforce

- Ignoring the backend — sovereignty is not just about apps or content, but cables, firmware, protocols, and chipsets

Strategic Insight for Policymakers:

You cannot govern what you do not own.

And you cannot protect what you do not understand.

Southeast Asia must recognize that digital sovereignty is a precondition to political independence.

The longer the region delays structural action, the more deeply control will be embedded — invisibly, irreversibly, and beyond negotiation.

The Real Choice: Design or Default

In the next decade, ASEAN will either be:

- A market shaped by others, with governance outsourced to foreign architecture

- Or a sovereign digital region, defining its own standards, rules, and alliances

There is no third path.

IX. Conclusion: Memory is Power. Signal is Control.

Southeast Asia is no stranger to survival.

For centuries, its nations have navigated empire, ideology, and occupation — not by meeting force with force, but by cultivating strategic ambiguity, managing complexity, and absorbing pressure without rupture.

But this moment is different.

In the digital domain, survival requires precision, speed, and design.

Ambiguity is no longer an asset — it is a liability. The invisible layers of power — code, cables, protocols, cloud — do not wait for consensus. They consolidate beneath the surface, quietly reshaping the very idea of sovereignty.

This essay began with a warning: that digital sovereignty is no longer theoretical. It is the frontier of strategic control in Southeast Asia. We’ve seen how China’s Digital Silk Road entrenches quietly. How the U.S.–aligned infrastructure offers conditional alternatives. How ASEAN’s internal fragmentation leaves the region systemically exposed.

And we’ve shown that only deliberate action — not rhetorical declarations — will secure the region’s autonomy.

The three strategic futures presented are not predictions.

They are options.

- Remain fragmented, and Southeast Asia will become a client zone to global architectures it does not own.

- Build coalitions, and a regional spine can form — one that others will connect to.

- Design sovereign systems, and ASEAN may once again define a new model of strategic non-alignment — this time, in code.

The region must now decide what kind of memory it wants to preserve, and what kind of signal it is willing to send.

Because in the digital world, there is no neutral space.

Every platform carries its own protocol.

Every infrastructure embeds its own logic.

Every signal reveals its source.

To lose control of that signal is to lose the ability to govern — not just data, but direction. Not just territory, but time.

For those watching this region — its diplomats, engineers, policy architects, and institutional strategists — the message is clear:

Southeast Asia’s autonomy will not be preserved by tradition.

It must be re-coded — deliberately, collectively, and urgently.