Executive Takeaways

1. ASEAN’s core strength — strategic ambiguity — is eroding as the Indo-Pacific fractures into competing security, economic, and digital blocs.

2. External powers are no longer coordinating through ASEAN. They are bypassing it via QUAD, AUKUS, the Digital Silk Road, and miniliteral trade-security corridors.

3. ASEAN’s institutional design cannot adapt fast enough: consensus becomes paralysis, neutrality becomes weakness, and sovereignty becomes hollow.

4. Southeast Asia is entering a structural alignment crisis — not because it chose sides, but because the architecture of choice is dissolving.

States like Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines are already partially aligned through defense, tech, or trade dependencies — splitting ASEAN from within.

5. Unless ASEAN reinvents itself or forms sovereign mini-orders, it risks strategic irrelevance in the very region it was created to stabilize.

I. Introduction: From Regional Platform to Global Bypass

Southeast Asia’s vaunted role as a neutral hub is under siege from an Indo-Pacific alignment crisis that is unfolding faster than any diplomatic manual anticipated. Once the lynchpin of a balanced U.S.-China hedge, ASEAN now finds its strategic value hollowed out by competing multilateral architectures and monoliteral pacts that bypass its consensus machinery.

The heart of this Indo-Pacific alignment crisis lies in the collision between traditional ASEAN mechanisms—non-alignment, non-interference, and consensus—and new networked empires that wrote their own rules. China’s Digital Silk Road Indo-Pacific strategy quietly embeds state-aligned infrastructure across the region.

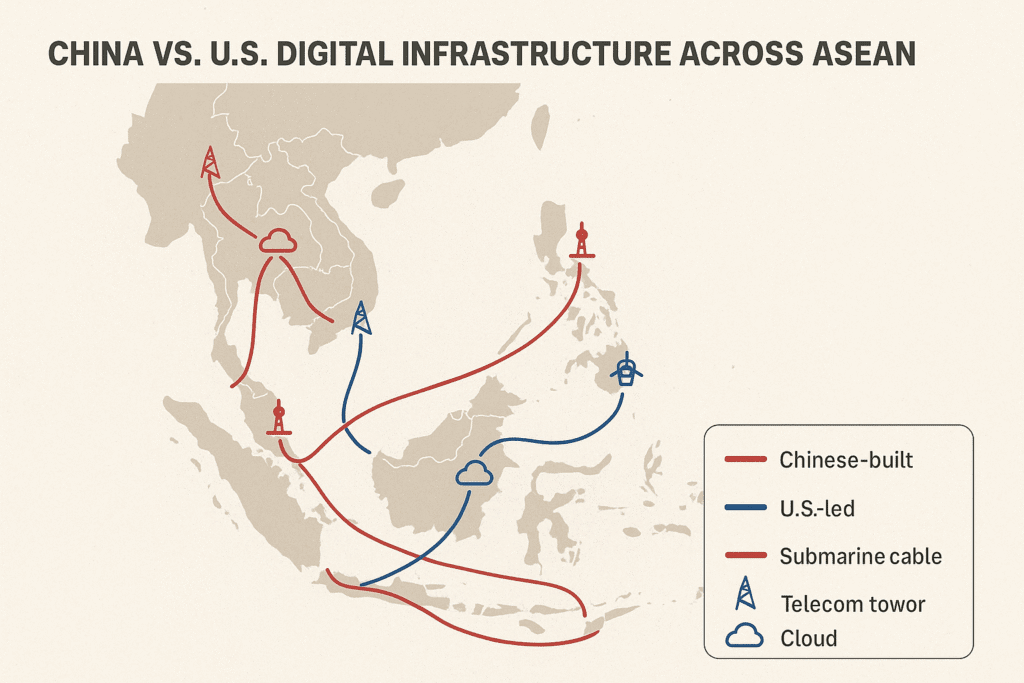

Meanwhile, the QUAD vs ASEAN dynamic pushes U.S.-led security and digital corridors through the very states ASEAN once courted in multilateral forums. The ASEAN strategic fracture is no longer theoretical: it is visible in submarine cables laid under separate bilateral schemes, defense logistics built outside ASEAN platforms, and digital rulesets negotiated one on one.

The original promise of an ASEAN “centrality” stemmed from its ability to convene—all major powers would meet under one roof. But today, that roof is cracked. As the U.S. launches AUKUS and IPEF, and Europe advances its Global Gateway, ASEAN’s platforms like the East Asia Summit and the ASEAN Regional Forum struggle to define any substantive agenda. Even economic integration—once ASEAN’s unassailable domain through RCEP and CPTPP—is being partially supplanted by specialized trade-security clusters among Japan, India, and Australia.

This paper will argue that the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis has three drivers:

- Competing Infrastructure Ecosystems: China and the U.S. are not just allies or rivals—they are building parallel architectures of power. From 5G networks to cloud data centers and digital currency rails, ASEAN states are forced to choose pieces of each, creating fragmented dependencies rather than unified sovereignty.

- Institutional Paralysis: ASEAN’s consensus model was designed for an earlier era of incremental confidence building. It cannot keep pace with the speed of the QUAD vs ASEAN security decoupling or the conditional integration of IPEF’s digital rules and the Digital Silk Road’s surveillance nodes.

- Minilateral Momentum: As minilateral pacts proliferate—Vietnam-Japan-Philippines defense linkages, Indonesia-Australia cyber agreements, and the Singapore-EU digital partnership—ASEAN’s collective alignment capacity atrophies, deepening the ASEAN strategic fracture.

The stakes of this Indo-Pacific alignment crisis are existential. If ASEAN cannot reconfigure itself—or forge one or more Digital Non-Alignment Doctrine frameworks—the region risks becoming a patchwork of client states. Sovereignty will be outsourced to infrastructure providers; policy autonomy ceded to external rulesets; and the very idea of ASEAN centrality reduced to a ceremonial relic.

In the following sections, we will:

- Map the rise of networked empires (China’s BRI 2.0 vs AUKUS/IPEF),

- Diagnose the ASEAN institutional fracture and its impact on regional centrality,

- Expose how states are being aligned by infrastructure, not just ideology,

- Chart emerging mini-orders and their disruptive effect on ASEAN unity,

- Present collapse scenarios and outline pathways for ASEAN to reinvent its strategic architecture.

The Indo-Pacific alignment crisis is accelerating. Understanding its drivers and potential futures is not an academic exercise—it is a roadmap for policy survival in the world’s most dynamic region.

II. The Rise of Networked Empires: Competing Architectures of Power

The Indo-Pacific alignment crisis is powered by two rival approaches to regional governance—China’s Digital Silk Road Indo-Pacific and the United States-led QUAD vs ASEAN architecture—each built around its own networked ecosystem of infrastructure, finance, and policy norms. ASEAN’s conventions were never meant to manage systemic competition conducted through cables, cloud servers, and coded standards. Today, those conventions are being tested by new “networked empires” that bypass multilateral consensus in favor of direct, programmable influence.

1. China’s Digital Silk Road Indo-Pacific

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has evolved from physical transport links into the Digital Silk Road Indo-Pacific: a full-stack ecosystem that extends from undersea cables to smart-city platforms, from national data centers to AI surveillance tools. Key elements include:

- Submarine Cable Investments

China’s Fiber-Optic Sea Express routes connect mainland China to Myanmar, Thailand, and Malaysia, providing exclusive routing agreements that guarantee priority bandwidth—and create chokepoints for any state seeking alternative backhaul. - 5G and Telecom Dominance

Huawei and ZTE equipment power major 5G deployments in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. By owning both hardware and management software, these vendors effectively control network diagnostics, maintenance, and (in extremis) throttling or shutdown. - State-Aligned Cloud Services

Huawei Cloud, Alibaba Cloud, and China Telecom’s CTCloud host critical government data for multiple ASEAN states. Under China’s National Intelligence Law, these platforms must cooperate with state security requests—creating legal avenues for off-shore data access. - Smart City Surveillance Exports

From Phnom Penh’s traffic-monitoring grid to Yangon’s facial-recognition pilot zones, Chinese smart-city contracts embed surveillance modules that can be remotely updated—normalizing foreign access to citizen data.

This expansion is sold as development and connectivity. In reality, it builds a parallel system of control beneath ASEAN’s radar. By the time governments perceive strategic vulnerability, it is too costly to rip out the hardware, re-lay cables, or migrate entire digital services.

2. The U.S.-Allied QUAD vs ASEAN Model

In response, the United States and its QUAD partners (Japan, Australia, India) have mobilized their own networked empire to secure “trusted” digital and defense corridors:

- Clean Network and Trusted Connectivity

The U.S. Clean Network initiative excludes “untrusted vendors” (mainly Huawei) from partner networks. It couples export controls on chips with diplomatic demands for vendor transparency—forcing states to choose between access to U.S. technologies or Chinese hardware. - QUAD Infrastructure and Cybersecurity Collaboration

Through joint exercises, capacity-building grants, and the Quad Digital Connectivity Partnership, the QUAD provides technical assistance for submarine cable projects (e.g., INDIGO-West), secure satellite broadband (e.g., OneWeb), and cybersecurity training to ASEAN militaries and agencies. - Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF)

While not a traditional free-trade agreement, IPEF’s digital trade and data governance pillar commits signatories to cross-border data flow principles, privacy safeguards, and non-localization clauses—creating a policy architecture that competing states must align with or risk exclusion. - AUKUS and Technology Sharing

Australia’s AUKUS pact adds downstream technology transfers (e.g., undersea drones, quantum communications) to the regional security mix. Though not directly digital governance, AUKUS underscores the U.S. commitment to advanced-tech partnerships—an implicit standard for “trusted” allies.

These initiatives are framed as “open” and “interoperable,” but they come with closed expectations: adherence to U.S. export regimes, intelligence-sharing agreements, and compatibility with U.S. cloud and platform ecosystems. States that sign on gain assured access to advanced capabilities—but trade away degrees of policy autonomy.

3. The New Architecture Landscape

China’s and the QUAD’s models are not mirror images; they operate on different logics:

| Dimension | Digital Silk Road Indo-Pacific | QUAD-IPEF Ecosystem |

| Infrastructure | Vendor-owned, turnkey, surveillance-ready | Open-tender cables, satellite hybrid |

| Cloud Services | State-aligned clouds with security law | Commercial clouds under export control |

| Standards & Protocols | China’s New IP, proprietary AI frameworks | Open Internet protocols, GDPR-style privacy |

| Policy Levers | Debt-for-tech swaps, conditional contracts | Export controls, capacity grants |

| Pace & Flexibility | Rapid deployment, opaque maintenance | Gradual rollout, transparent oversight |

This dual-track reality leaves ASEAN in the middle of a tug-of-war. Each state faces contrasting incentives: lower cost and speed from China, versus conditional trust and premium technology from the U.S. system. The result is not a balanced hedge but a fragmented alignment, where states pick and choose components, creating a patchwork of dependencies that erode collective autonomy.

In the next section, we examine how these competing architectures collide with ASEAN’s aging institutional model—revealing why its consensus-based design is ill-equipped for the velocity and opacity of the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis.

Submarine cables, telecom towers, and cloud nodes illustrate competing architectures vying for control.

III. ASEAN’s Institutional Fracture: The Doctrine No Longer Fits

The Indo-Pacific alignment crisis does not play out only in hardware and cables—it plays out in institutions. ASEAN’s founding design—non-alignment, non-interference, and consensus—was crafted for an era of slower, state-led diplomacy. Today, these pillars are buckling under the velocity and opacity of networked power. This echoes the limits of ASEAN’s Quiet Doctrine, where consensus now stalls action.

1. Consensus Paralysis

ASEAN’s signature consensus rule requires unanimity for major declarations. This mechanism once prevented great-power divide-and-rule tactics. Now, it paralyzes:

- South China Sea Stalemate: Attempts at a joint communiqué on freedom of navigation routinely collapse when any member, under external pressure, withholds agreement, reinforcing the very coercion consensus was meant to deter.

- Digital Regulations: Proposals for region-wide data governance or cybersecurity standards never move past working groups because a single dissenting state can veto progress.

- Crisis Response: When urgent threats arise—from cyberattacks on power grids to maritime skirmishes—ASEAN’s ministerial body cannot issue timely, unified guidance.

In effect, consensus has become a tool of veto for external actors and recalcitrant members, deepening the ASEAN strategic fracture.

2. Non-Interference vs. Collective Security

The principle of non-interference, designed during the Cold War to protect fledgling states from external meddling, now ensures ASEAN cannot act when member actions threaten regional stability:

- Myanmar Coup Response: The Five-Point Consensus imposed no meaningful consequences, as any push for suspension ran into the non-interference wall. External partners lost faith; the crisis festered.

- Taiwan Contingencies: Even as tensions rise in the Taiwan Strait, ASEAN refuses to consider a joint response or humanitarian corridor, fearing it might contravene non-interference or provoke alignment.

Non-interference, once a shield, has become a straitjacket that undermines ASEAN’s capacity to safeguard its collective interests.

3. Eroding Centrality

ASEAN’s claim to centrality—its role as the primary forum for regional dialogue—is slipping:

- QUAD and AUKUS Exclusion: Key security arrangements operate entirely outside ASEAN’s mechanisms, signaling to member states that their most critical strategic decisions will be made elsewhere.

- Digital Silk Road Summits: China holds bilateral digital cooperation forums that bypass ASEAN’s digital working groups, drawing technocrats and policymakers away from established ASEAN channels.

- IPEF Political-Economic Pillars: U.S.-led economic frameworks require direct participation, creating parallel tracks that run around ASEAN’s Economic Community architecture.

As external platforms proliferate, ASEAN’s multilateral venues host photo-ops but seldom real policy actions, deepening the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis by sidelining the very forum meant to manage it.

4. Fragmented Agency, Fragmented Alignment

The combined effect of consensus paralysis, rigid non-interference, and diminishing centrality is an ASEAN strategic fracture in which:

- Individual States make alignment choices unilaterally—signing bilateral defense accords, adopting foreign digital standards, or granting exclusive economic zones to external powers.

- Regional Cohesion erodes as member interests diverge, with maritime and mainland states facing different threats and incentives.

- Institutional Irrelevance sets in as domestic capitals bypass ASEAN for more responsive, targeted minilateral or bilateral engagements.

Without swift institutional adaptation, ASEAN will not manage the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis—it will be overtaken by it.

5. Toward Institutional Reinvention

ASEAN must evolve—or watch its founding framework become a relic:

- Flexible Consensus: Adopt super-majority voting for critical domains (e.g., cybersecurity, maritime security) so that a single veto cannot stall collective defense.

- Conditional Non-Interference: Allow for graduated intervention when member actions—cyberattacks, territorial incursions, democratic erosion—pose systemic risks.

- Centrality Through Strength: Reinforce ASEAN’s convening power by establishing rapid-response teams, joint procurement programs (e.g., regional cyber rescue squads), and a digital secretariat capable of real-time coordination.

These reforms can repair the ASEAN strategic fracture, restoring its ability to manage the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis on its own terms.

Having diagnosed the institutional breakdown at ASEAN’s core, the next section examines how physical and digital infrastructures are aligning states one at a time—shaping a patchwork of dependencies that further undermine collective agency.

IV. Alignment by Infrastructure: How Sovereignty Is Quietly Absorbed

ASEAN’s institutional paralysis sets the stage—but the real force reshaping the region isn’t diplomacy. It’s infrastructure, the silent conveyor of influence that aligns states before they even realize it. The stakes of the digital sovereignty in Southeast Asia debate are already clear that in this Indo-Pacific alignment crisis, who controls the cables, the clouds, and the code wields the true levers of power.

1. Military Logistics and Defense Footprints

- Philippines–U.S. Enhanced Defense Cooperation

Under EDCA, U.S. forces gain rotating access to key bases—complete with hardened communications links, satellite terminals, and logistics nodes. These physical assets double as digital hubs, embedding American command-and-control networks within Philippine territory. - Vietnam–Japan–India Triangular Exercises

Tri-lateral drills now include secure data-sharing protocols and AI-powered maritime surveillance platforms, binding partner militaries into a shared digital defense grid—effectively aligning Vietnam’s defense infrastructure with QUAD standards. - Indonesia–Australia Undersea Cable

The proposed INDIGO network not only boosts bandwidth but also installs encryption gateways operated by Australian firms, ensuring any sensitive data traffic over the Java Sea traverses “trusted” nodes.

In each case, defense cooperation isn’t just about troops; it’s about hardware—and the rule sets baked into it.

2. Telecom and 5G Networks

- Myanmar’s Chinese-Built 5G Core

The junta’s telecom regulator granted Huawei exclusive rights to deploy 5G core networks—handing China the ability to manage routing, prioritize packets, and, if needed, throttle or isolate segments of the national grid. - Singapore’s Multi-Vendor Policy

Singtel runs a “vendor-diversity” model: Cisco, Ericsson, Huawei, Nokia all co-exist under strict interoperability standards. This ensures no single vendor can disable critical services unilaterally—and positions Singapore as a hub for cross-ecosystem trials. - Thailand’s Dual-Stack Rollout

Bangkok’s telecom regulator issues parallel licenses to Chinese and Western 5G providers—but experimental spectrum auctions have forced compliance with both Chinese security protocols and EU-style privacy norms, creating a hybrid alignment.

Telecom infrastructure choices thus encode geopolitical preference at the lowest level of national connectivity.

3. Cloud and Data Centers

- Vietnam’s Local Cloud Mandate

Decree 72 and the subsequent Cloud First policy require government agencies to use domestic cloud providers. In practice, these providers partner with AWS and Google for underlying services, creating a layered dependency that blends local control with foreign architecture. - Malaysia’s National Data Center Network

Deployed by a consortium of European and Chinese firms, Malaysia’s Pusat Data Negara links provincial hubs via fiber funded by the EU’s Global Gateway and China’s New Digital Silk Road—tying Kuala Lumpur’s data policies to both blocs simultaneously. - Philippines’ Digital Infrastructure Fund

A state-backed fund incentivizes joint ventures between U.S. hyperscalers and local telcos, embedding American cloud-native security frameworks into e-government services.

Cloud strategy is no longer simply a cost-efficiency exercise; it is a sovereignty test.

4. Payment Rails and CBDC Corridors

- Cambodia’s Bakong System

Built by Chinese developers on UPI-inspired rails, the Bakong platform interlinks banks and mobile wallets—but transactions clear through a Chinese-hosted settlement layer, giving Beijing realtime visibility into Cambodian flows. - Singapore’s FAST Payment Network

Operated by MAS, FAST connects domestic and cross-border wallets, with secure APIs that European and U.S. fintechs must integrate to access ASEAN liquidity. It exemplifies “open” alignment with Western standards. - Indonesia’s Bank Indonesia Digital Rupiah Pilot

Leveraging a domestic CBDC framework tested in partnership with UK fintechs, Indonesia positions itself at the intersection of ASEAN’s contrasting payment ecosystems.

Digital money bridges commerce and control—and sets the terms for who can transact, when, and under what rules.

Strategic Insight

Infrastructure isn’t neutral. Each cable laid, each data node built, and each API connected carries an implicit treaty—binding the host state into an alignment whose terms are encoded in code and contracts. As ASEAN states chase capacity, speed, and foreign investment, they must recognize that every infrastructure choice is a geopolitical alignment decision.

In the next section, we examine how minilateral coalitions are emerging precisely to regain agency—crafting their own infrastructure pacts outside both ASEAN and the great-power binaries.

| Country | Telecom (5G/Core) | Cloud Infrastructure | Data Governance | AI / Policy Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnam | U.S.-leaning | AWS, Google | Local control, Western-aligned | Drafting AI framework |

| Singapore | Neutral | AWS, Azure, Alibaba | GDPR-compatible | Leading AI ethics |

| Indonesia | Mixed | AWS, Huawei | Emerging | U.S. and China influence |

| Cambodia | Chinese | Huawei Cloud | Chinese-aligned | Smart city model (China) |

| Laos | Chinese | Chinese-only | No regulation | None |

| Malaysia | Mixed | Google, Azure | Draft stage | Passive |

| Philippines | U.S.-leaning | Google, Azure | Pro-West | Pro-U.S. |

| Thailand | Mixed | Multiple | No clear framework | Low activity |

| Myanmar | Chinese | Chinese | Military-controlled | Surveillance-heavy |

| Brunei | Neutral | Minimal | Passive | Minimal |

Table: Tele-/Cloud/Governance/AI posture by country — shows how each ASEAN state’s telecom, cloud, data and AI policies align with Chinese or U.S. ecosystems.

V. Mini-Orders Are Rising: Regional Coalitions Below the ASEAN Level

When ASEAN itself cannot adapt rapidly, like-minded states are forming minilateral coalitions—focused, flexible alliances built around specific strategic domains. These mini-orders bypass ASEAN’s consensus gridlock and lay the groundwork for new regional alignments.

1. Vietnam–Japan–Philippines Security Convergence

- Joint Cyber Defense Exercises: Annual trilateral drills now include cyber-range simulations, enabling each military to share threat intelligence and incident-response protocols.

- Secure Satellite Communications: A new partnership underwrites a shared satellite-link network, ensuring wartime resilience independent of any single provider.

- Logistics Interoperability: Port and airfield upgrades funded by Japan hinge on compatible digital command systems deployed by the Philippines, knitting three defense architectures into a cohesive subgroup.

2. Indonesia–Australia AI & Data Cooperation

- Cybersecurity Center of Excellence: Canberra and Jakarta co-host a regional training hub, standardizing AI-powered threat detection tools for government agencies across SEA.

- Data Governance Framework: A joint working group drafts binding guidelines on data privacy and cross-border data flow, blending EU-style protections with ASEAN pragmatism.

- Research & Development Grants: Shared funding for edge-computing labs in Batam and Perth accelerates local innovation—reducing dependency on foreign cloud monopolies.

3. Singapore–UK–EU Digital Partnership

- Digital Economy Agreement Expansion: Beyond trade, the tripartite pact now covers digital identity standards, fintech interoperability, and joint AI ethics codes.

- Regulatory Exchange Program: EU regulators shadow MAS officials, while Singaporean policymakers study GDPR enforcement—spinning knowledge networks that embed Western norms.

- Innovation Sandbox Networks: Cross-jurisdiction sandboxes allow startups to test products under aligned compliance regimes, creating de facto common technical standards.

4. Philippines–South Korea Telecommunications Initiative

- 5G Security Taskforce: Manila and Seoul co-sponsor an initiative vetting telecom vendor against shared criteria—ensuring no single actor dominates the Filipino spectrum.

- Rural Connectivity Grants: Joint funding for South Korean small-cell deployments in Philippine provinces diversifies infrastructure sources and strengthens local sovereignty.

Why Mini-Orders Matter

- Speed & Depth: Unlike ASEAN’s broad but slow deliberations, minilateral groups deliver concrete capability upgrades and integrated systems within months.

- Scalable Inclusion: These coalitions can invite additional members or observers—laying a path for eventual ASEAN-wide adoption without initial unanimity.

- Strategic Signaling: By building these networks, core states signal their policy preferences clearly to major powers, forcing external actors to respect negotiated terms rather than impose them bilaterally.

Strategic Insight

Minilateral coalitions are not new. What’s different is their digital and defense focus—fields where technological lock-in happens at machine speed. These mini-orders act as testbeds for alternative architectures, demonstrating that sovereign alignment can be constructed from the bottom up, rather than waiting for an impaired ASEAN consensus.

Having seen how minilateral groups are stitching together resilience, our next section will explore collapse scenarios—what happens if neither ASEAN reform nor mini-orders can contain the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis.

VI. ASEAN Collapse Scenarios: When Centrality Fails

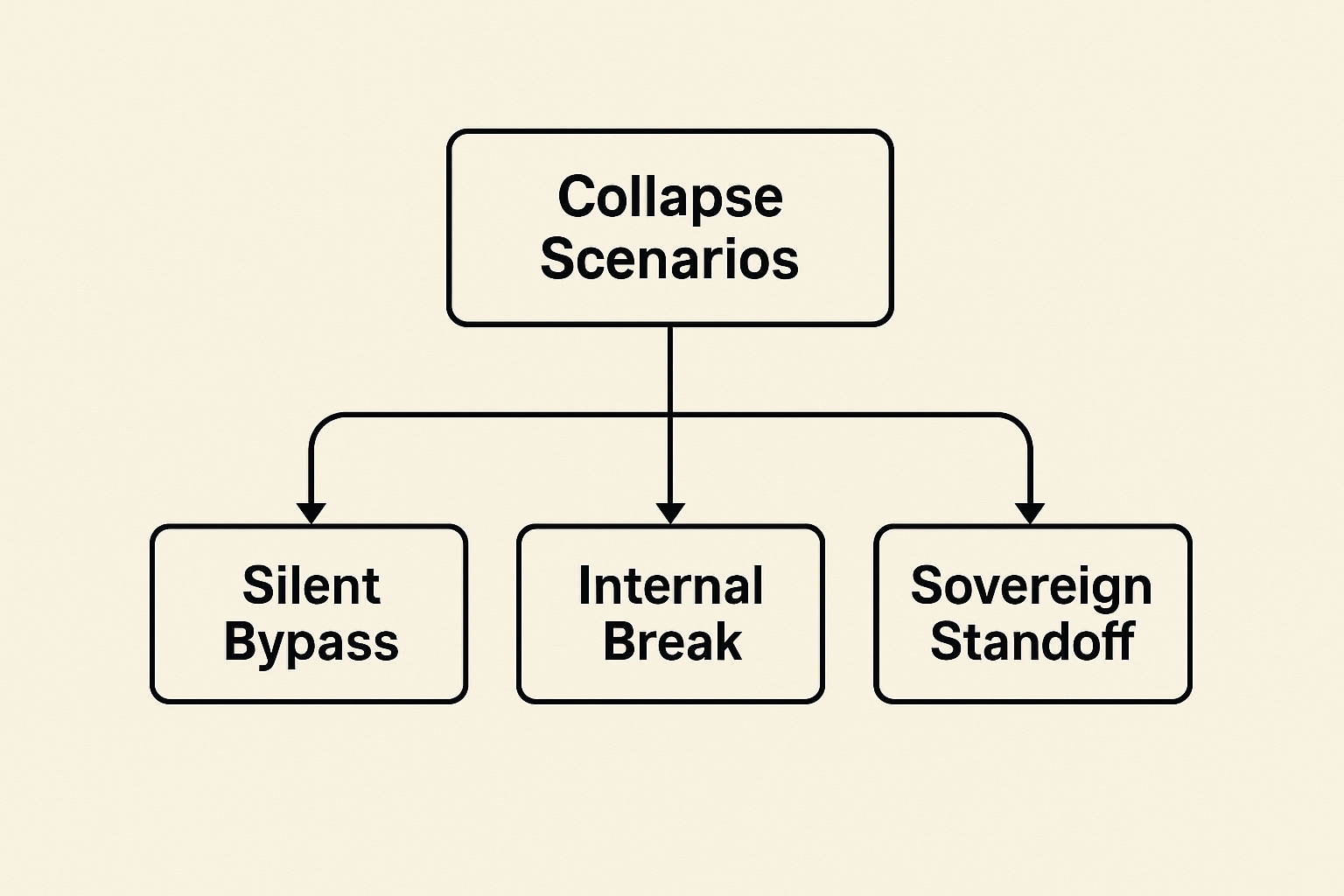

If neither institutional reform nor minilateral coalitions can arrest the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis, ASEAN risks sliding into one of three collapse scenarios—each marking a different path toward strategic irrelevance or fragmentation.

1. Silent Bypass: ASEAN as Photo-Op Venue

What It Looks Like

- Major powers continue to meet in “ASEAN-based” forums, but all substantive agreements are struck bilaterally or in minilateral groups.

- ASEAN’s summits become backdrops for external announcements (e.g., new QUAD projects, Digital Silk Road signings), while the bloc issues only generic communiqués.

Consequences

- ASEAN retains diplomatic visibility but loses policy influence.

- Member states prioritize external venues over ASEAN mechanisms, deepening the ASEAN strategic fracture.

- Younger diplomats and technocrats see ASEAN pathways as career dead ends.

Trigger Conditions

- Continued consensus paralysis on key issues (South China Sea, cyber norms).

- An external crisis (e.g., Taiwan conflict spillover) addressed exclusively through QUAD or AUKUS, sidelining ASEAN’s crisis processes.

2. Internal Break: Factional Realignment

What It Looks Like

- A subset of ASEAN states (e.g., Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia) form a de facto “core ASEAN” with explicit security and digital cooperation agreements.

- Other members (e.g., Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar) deepen alignment with China—possibly forming their own sub-bloc or even exiting key ASEAN frameworks.

Consequences

- ASEAN’s unity splinters into competing factions, each with its own external patrons.

- The original ASEAN Charter is openly challenged; some members begin to question the value of participation.

- Regional development funds, trade facilitation, and digital integration stall in contested zones.

Trigger Conditions

- One or more members publicly breach ASEAN norms (e.g., vetoing defense support for frontline states).

- A targeted external inducement (massive BRI loan, security guarantees) prompts a member to shift allegiance.

3. Sovereign Standoff: Crisis Beyond ASEAN’s Capacity

What It Looks Like

- A major cross-border cyberattack or military incident occurs (e.g., a subsea cable sabotage or contested island skirmish).

- ASEAN’s existing crisis protocols (Five-Point Consensus, ARF statements) prove too slow or toothless to coordinate an effective response.

- Frontline states act unilaterally or through minilaterals; other members watch from the sidelines or align with external powers for protection.

Consequences

- ASEAN’s credibility collapses among both members and external partners.

- External actors fill the vacuum—establishing permanent defense and digital outposts inside member states.

- Regional order bifurcates; small states choose side-car status under U.S., Chinese, or hybrid security umbrellas.

Trigger Conditions

- Simultaneous crises in multiple domains (cyber, maritime, political) overwhelm ASEAN’s slow-moving machinery.

- A major external power directly challenges ASEAN’s unity (e.g., demands collective condemnation or backing in a geopolitical contest).

Common Fallout Across Scenarios

Across all three collapse modes, ASEAN’s centrality erodes into either a ceremonial role or an outright broken governance structure. National sovereignty is hollowed by dependencies on external infrastructure and security guarantees. Collective bargaining power vanishes, replaced by a mosaic of client-patron relationships.

Strategic Insight for Policymakers

Collapse is not a singular event but a process.

It begins with subtle bypasses, deepens through factional rifts, and can culminate in outright institutional irrelevance when crisis strikes.

Understanding these trajectories allows ASEAN and its member states to anticipate fracture points and deploy reform or minilateral countermeasures before centrality is irrevocably lost.

The final section will present pathways for ASEAN 2.0—redesigning its strategic architecture for the digital-security nexus, restoring centrality by building new protocols in code, coalition, and crisis response.

VII. ASEAN 2.0 or Fracture? Designing a Sovereign Future

Facing the stark collapse scenarios of the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis, ASEAN must choose between further fragmentation or a bold reinvention—ASEAN 2.0. This upgraded architecture must embed digital and security sovereignty into every layer, transforming the bloc from a passive convenor into an active shaper of regional order.

Even though ASEAN’s own Digital Masterplan 2025 outlines the need for a unified data governance framework, we would like to propose additional points from our perspectives.

1. The ASEAN Tech Compact: A New Digital Commons

Purpose: Forge a binding framework for cloud, data, and cybersecurity that all ten members adopt.

- Shared Cloud Infrastructure:

Establish an ASEAN-owned hyperscale cloud consortium. Each state contributes data-center capacity and agreed-upon open-source software, reducing reliance on U.S. or Chinese providers. - Common Data Governance Laws:

Harmonize privacy, localization, and cross-border data flow regulations under a unified ASEAN Digital Act. This closes legal loopholes exploited in the China Digital Silk Road Indo-Pacific and QUAD vs ASEAN arenas. - Regional Cyber Defense Authority:

Create a joint operations center with real-time threat monitoring, incident response playbooks, and a collective “rapid reaction cyber unit” to counter state-sponsored attacks.

Impact: A Tech Compact reverses digital fragmentation and positions ASEAN as a single market for “trusted” tech investment—addressing the ASEAN strategic fracture head-on.

2. The ASEAN Defense Quadrant: Flexible Security Alignment

Purpose: Implement a graduated decision-making process for defense cooperation that respects non-interference while enabling collective action.

- Tiered Consensus Mechanism:

For high-impact threats (maritime incursions, cyber-warfare, humanitarian crises), shift from unanimity to a two-thirds majority rule, accelerating joint responses. - Rotational Command Nodes:

Designate rotating lead states (e.g., Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia) to coordinate multilateral exercises, intelligence sharing, and logistics support—ensuring no single power can veto basic security commitments. - Interoperability Standards:

Mandate all member militaries adopt compatible communications protocols and secure data links modeled on QUAD-developed frameworks, but managed within ASEAN structures.

Impact: The Defense Quadrant preserves ASEAN’s non-alignment spirit by allowing a flexible coalition for existential threats—avoiding both blockade by consensus and unilateral external basing.

3. ASEAN Memory Infrastructure: Signal Sovereignty

Purpose: Institutionalize shared “memory” systems—data archives, research networks, and foresight platforms that anchor ASEAN’s collective identity.

- Blockchain-Backed Regional Registry:

Launch an immutable ledger for cross-border agreements (trade, security, digital law), ensuring transparency and reducing external manipulation of records. - Strategic Foresight Observatory:

Fund an ASEAN Futures Lab that combines AI-driven scenario modeling (covering climate, cyber, and geopolitical risks) with annual “ASEAN Futures Summit” reports—informing policy in real-time. - Cultural-Digital Exchange Hubs:

Build distributed digital museums and archives that preserve regional heritage and foster pan-ASEAN data literacy—strengthening public buy-in for shared protocols.

Impact: Memory Infrastructure cements ASEAN as an intellectual and digital commons, making it harder for external powers to rewrite regional narratives or isolate member states.

4. Implementation Roadmap & Political Will

To activate ASEAN 2.0, leaders must:

- Declare a New Charter Addendum: A special summit resolution that commits to the Tech Compact, Defense Quadrant, and Memory Infrastructure within a defined timeline (e.g., 24 months).

- Establish a High-Level Task Force: Chaired by rotating heads of state with a permanent secretariat empowered to draft regulations and monitor compliance.

- Secure Seed Funding: Leverage contributions from member-state development banks, plus co-investment from committed external partners under clear, sovereignly-governed terms.

- Embed in National Law: Require each member to transpose ASEAN 2.0 elements into domestic legislation—ensuring enforceability at home and credibility abroad.

Strategic Insight

ASEAN’s original non-alignment doctrine was a profound innovation of its time. Today, an ASEAN 2.0 doctrine—one of digital sovereignty, flexible security, and collective memory—can reclaim regional agency amid the Indo-Pacific alignment crisis. The choice is not between alignment and neutrality, but between structural subservience and sovereign design.

VIII. Conclusion: Memory Is Power. Signal Is Control. Architecture Is Destiny.

The Indo-Pacific alignment crisis has exposed ASEAN’s vulnerabilities: an outdated institutional framework, fragmented member alignments, and an absence of shared digital and security architectures. Once celebrated for its strategic ambiguity, ASEAN now risks becoming a patchwork of client states, governed not by its own policies but by the infrastructures and protocols imposed by external powers.

Yet the crisis also presents an opportunity. By embracing ASEAN 2.0, the bloc can transform from a passive convenor into an architect of its own future. The proposed Tech Compact cements digital sovereignty; the Defense Quadrant restores collective security; and the Memory Infrastructure ensures ASEAN writes its own strategic narrative. These elements are not mere policy initiatives—they are the code, cables, and consensus that will preserve regional autonomy in the face of competing networked empires.

The path forward demands more than rhetoric. It requires decisive political will, institutional innovation, and cross-sector collaboration—national governments, private sector partners, and civil society working in concert. Each ASEAN state must see beyond short-term gains and recognize that sovereignty in the 21st century is embedded in systems, not slogans.

In the coming decade, Southeast Asia will either:

- Become a market for external architectures, or

- Forge its own sovereign framework, reclaiming the power of its code and the control of its signal.

The choice is clear.

Memory is power—the collective record of agreements and foresight tools that anchor regional strategy.

Signal is control—the digital pathways and policy protocols that determine influence.

And above all, architecture is destiny—the infrastructure we build today will decide who governs Southeast Asia tomorrow.

“Memory is Power. Signal is Control. Architecture is Destiny.”

Vietfuturus

1 Comment

Pingback: Thailand-Cambodia Political Scandal: ASEAN at a Crossroads